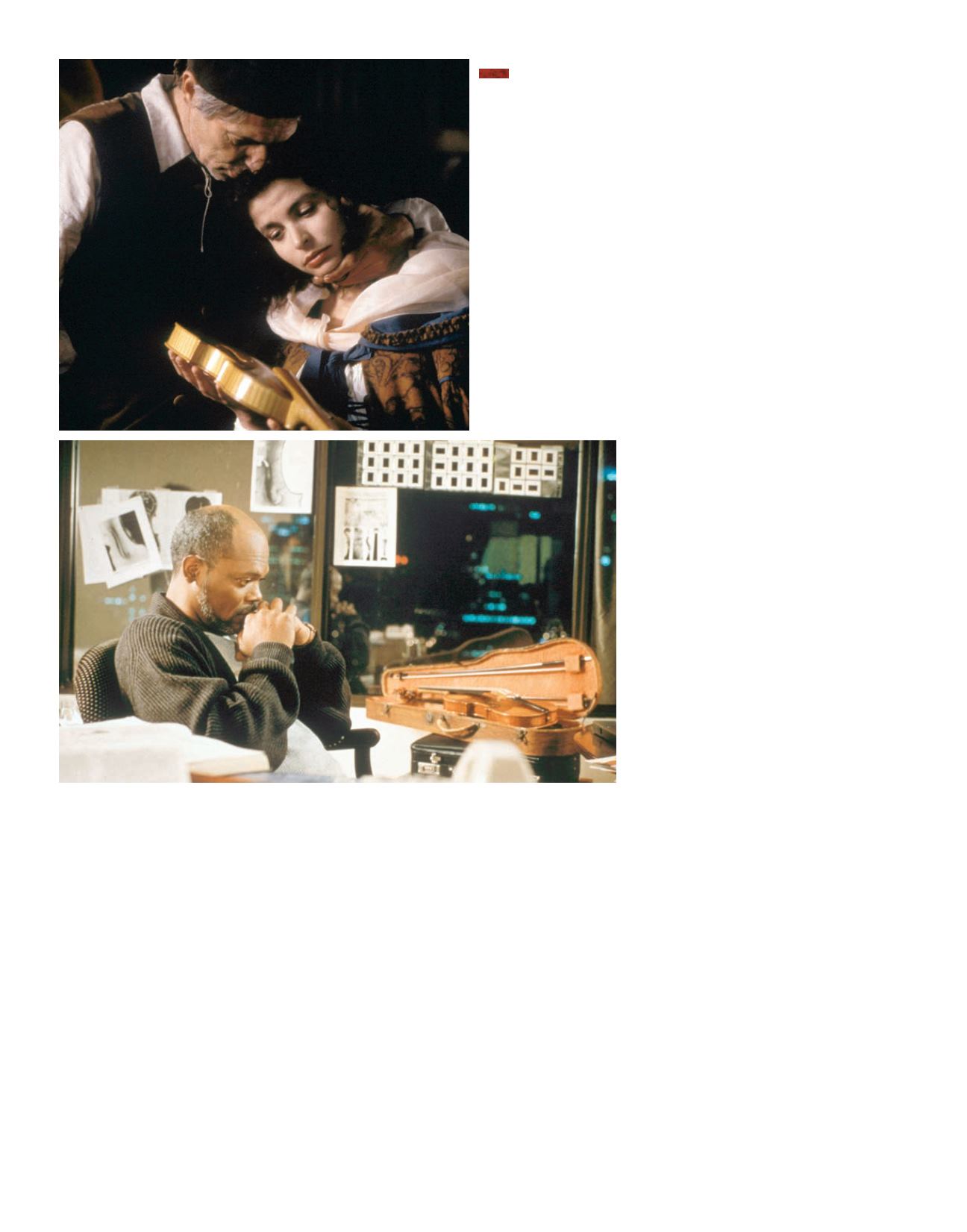

François Girard’s

The Red

Violin

traces the “life” of

a single violin, from its

creation at the hands of

Nicolò Bussotti (Carlo

Cecchi, left) in 1681 to its

modern-day ownership by

Charles Morritz (Samuel

L. Jackson, below). As in

the “life stories” of string

instruments created around

the same time by real-life

luthiers Amati, Rugeri,

Guarneri, and, of course,

Stradivari, the “Red Violin”

by Bussotti changed

hands by theft as often as

by legitimate means, a

mark of the unparalleled

desirability of these

instruments.

instrument of the symphony orchestra,

the violin has felt at home for centuries

in rural America, whether in folk music,

square dancing, bluegrass, or country/

western. And it works in both direc-

tions: acclaimed ddler Mark O’Connor

has taken the country ddle back into

classical concert venues, such as when

he performed the world premiere of his

Double Violin Concerto at Ravinia with

violinist Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg

and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Christoph Eschenbach in

August

.

e violin has another, surprisingly

dark, side, namely its identi cation with

death and the devil. e archangel Ga-

briel blows a trumpet, and saints strum

harps in heaven—but the devil plays a

violin. It has been theorized that this

association rst developed during the

Renaissance, when the violin frequently

provided accompaniment to peasant

dancing; and dance—in the eyes of both

Catholic and Protestant moralists—

was the creation of the devil (a notion

enshrined in the hit lm

Footloose

).

During the mid- th century, Giuseppe

Tartini attributed his inspiration for his

most famous sonata to a gi from the

devil. He claimed that in a dream the

devil gave him a violin, upon which

Tartini played a sonata of indescrib-

able beauty. His attempt to reconstruct

it upon awakening failed, but it did

result in the “Devil’s Trill” Sonata. And

during the following century, the violin

virtuosity of Nicoló Paganini was so

jaw-dropping that many listeners felt it

could only have been achieved with the

help of the Prince of Darkness.

e strings of a violin are tuned in

hs, and the eerily open and ambigu-

ous sound of that interval in amed the

morbid side of the Romantic aesthet-

ic. In his autobiography

Mein Leben

,

Richard Wagner recorded the ghostly

tremors he felt as a child while attending

concerts in Dresden: “ e mere tuning

up of the instruments put me in a state

of mystic excitement; even the striking

of hs on the violin seemed to me like

a greeting from the spirit world. … e

sound of these hs, which has always

excited me, was closely associated in my

mind with ghosts and spirits.” Wagner

magically recreated that experience in

the tremulous opening of the overture to

e Flying Dutchman

.

ose same hs open Franz Liszt’s

famous

Mephisto Waltz

No. , depicting

a scene from Goethe’s

Faust

in which

Mephistopheles enlivens a rustic wed-

ding with his own frenzied playing upon

a violin he has seized from a peasant.

Again one hears the devil in his incar-

nation as death tuning a violin at the

start of Camille Saint-Saëns’s orchestral

tone-poem

Danse Macabre

, inspired by

a poem by Henry Cazalis:

Zig and zig and zig! Hark, Death beats a

measure,

Drums on a tomb with heels hard and thin.

Death plays at night a dance for his pleasure

Zig and zig and zig! on his old violin.

Satan was still strung out on the vio-

lin in

, when Stravinsky composed

A Soldier’s Tale

. is time it is a mortal

soldier who gives the devil a violin in

exchange for unlimited wealth. And

as late as

, the devil challenged a

young country boy to a ddling contest

in the Charlie Daniels Band’s hit “ e

Devil Went Down to Georgia.” e boy

is promised a golden violin if he wins,

but he must forfeit his soul if he loses.

Apparently by this time Beelzebub’s

technique had deteriorated, because the

kid wins the golden ddle.

e concept of the aspiring violin

virtuoso pursuing a career at the ex-

pense of everything else in life seems to

© RHOMBUS MEDIA (BOTH)

RAVINIA MAGAZINE | AUGUST 20 – SE3TEM%ER 2, 2018

38