wrote to Henriette Voigt on August ,

, “if

their ‘stems’ and ‘lines’ are so tender and feeble.”

Elsewhere, Schumann described this trio of

works as “lighter and more feminine.” Others

noticed a stylistic change as well. Carl Kossm-

aly—a composer, critic, and original member of

Schumann’s

Davidsbund

(Society of David)—

published the rst comprehensive review of

Schumann’s music in the

Allgemeine Musika-

lische Zeitung

(

), in which he praised this

return to “melodic ow, clarity, and songlike

attitude.”

e

Arabeske

in C major, op. , is a seven-min-

ute rondo movement. Its C-major refrain pres-

ents a charming, memorable theme with con-

siderable internal repetition.

e rst episode

o ers a brooding Romantic melody in minor.

Schumann restates the refrain, and then intro-

duces additional thematic contrast with another

minor-key theme containing a rhythmic motive

from the refrain.

e refrain is heard a nal

time. A coda, apparently unrelated to previous

melodic material, concludes in an introspective

mood.

As for the fate of the

Neue Zeitschri für

Musik

, a er a six-month administrative review,

Schumann’s petition was rejected, and he de-

parted Vienna on April ,

.

Variations on a Nocturne by Chopin in

G minor, Anh:

Schumann frequently praised the compositions

of Polish Romantic pianist-composer Fryderyk

Franciszek Chopin in the pages of the

Neue

Zeitschri für Musik

, observing and document-

ing his progression from keyboard virtuoso to

introspective artist.

is evolution appeared

complete with the publication of Chopin’s Noc-

turne in G minor, op. , no. , as Schumann

elaborated in a review of recent piano compo-

sitions by Chopin, Schubert, and Mendelssohn:

“I shall merely observe that Chopin seems at last

to have arrived at the point which Schubert had

reached long before him. … Chopin’s virtuosity

now serves him. I shall add that Florestan [the

imaginary alter-ego in Schumann’s critical writ-

ing representing his passionate mind], some-

what paradoxically, declared that ‘in Beethoven’s

Leonora

Overture there was more future than in

his symphonies’; this remark may be more cor-

rectly applied to Chopin’s most recent Nocturne

in G minor, in which I detect the most terri c

declaration of war to the entire past; further-

more, one begins to ask oneself how gravity

must be clothed if jest goes about wrapped in

dark veils.”

Smaller compositional forms as hotbeds of mu-

sical revolution remained a common refrain for

Schumann, both as composer and critic. Beyond

the surface simplicity of Chopin’s nocturne, he

recognized a profound intensity of expression

and unconventionality of form, elements that

Schumann extended into his own Variations

on a Nocturne by Chopin in G minor, Anh:

.

Taking the opening section of Chopin’s G-minor

nocturne, Schumann began composing a series

of variations in

– , before stopping in the

middle of the

h variation.

is set remained

incomplete and unpublished in Schumann’s

lifetime.

Concert sans orchestre

in F minor, op. (

)

At various points in his career, Robert

Schumann attempted to break into the Vien-

nese musical market. e year

brought his

rst multi-pronged advance. On February ,

Schumann initiated negotiations with Tobias

Haslinger—one of the leading music publish-

ers in Vienna, whose catalog included import-

ant works by Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz

Schubert, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, and Ignaz

Moscheles, among numerous others—to issue

a grand sonata and etudes for solo piano.

at

correspondence stretched over a period of four

months. In October, Schumann dispatched the

rst three volumes of his musical journal, the

Neue Zeitschri für Musik

, to the Gesellscha

der Musikfreunde, ostensibly as a gi to the so-

ciety’s library but more surreptitiously to build

his reputation as a music critic.

e interactions with Haslinger, particularly

regarding the publication of Schumann’s new

piano sonata, provide exceptional insight into

the publication, dedication, and re-composition

process. A er sending the engraver’s copy of the

sonata to Haslinger on February , Schumann

wrote the piano virtuoso Ignaz Moscheles on

March to ask if he would accept the dedica-

tion of the published sonata. Schumann had

met Moscheles the previous October through

Felix Mendelssohn, a former student of the pi-

anist, and sought the elder musician’s approval

of the new composition. Moscheles accepted

the dedication but later gave a somewhat un-

favorable review in an article on the “New Ro-

manticism” published, ironically, in Schumann’s

Neue Zeitschri für Musik

, where he described

the work as “very labored, di cult, and rather

confused, but interesting.”

As originally submitted, the sonata contained

ve movements, two of which were scherzos.

Sometime between February and June, Hasling-

er evidently returned the manuscript with re-

quests for a number of changes, including the

removal of both scherzos, the omission of two

variations and reordering of the others in the

Quasi variazioni

movement, and the inclusion

of an alternate nale. Schumann had made these

adjustments and enlarged the coda in the rst

movement by the time he returned the man-

uscript to Haslinger in June. His revised score

included a new title in a handwritten note on

the rst page of music, where the composer had

crossed out “Sonate III” and substituted “Con-

cert.” Engraving followed, and the three-move-

ment score was published in November under

the title

Concert sans orchestre

, presumably the

suggestion of Haslinger.

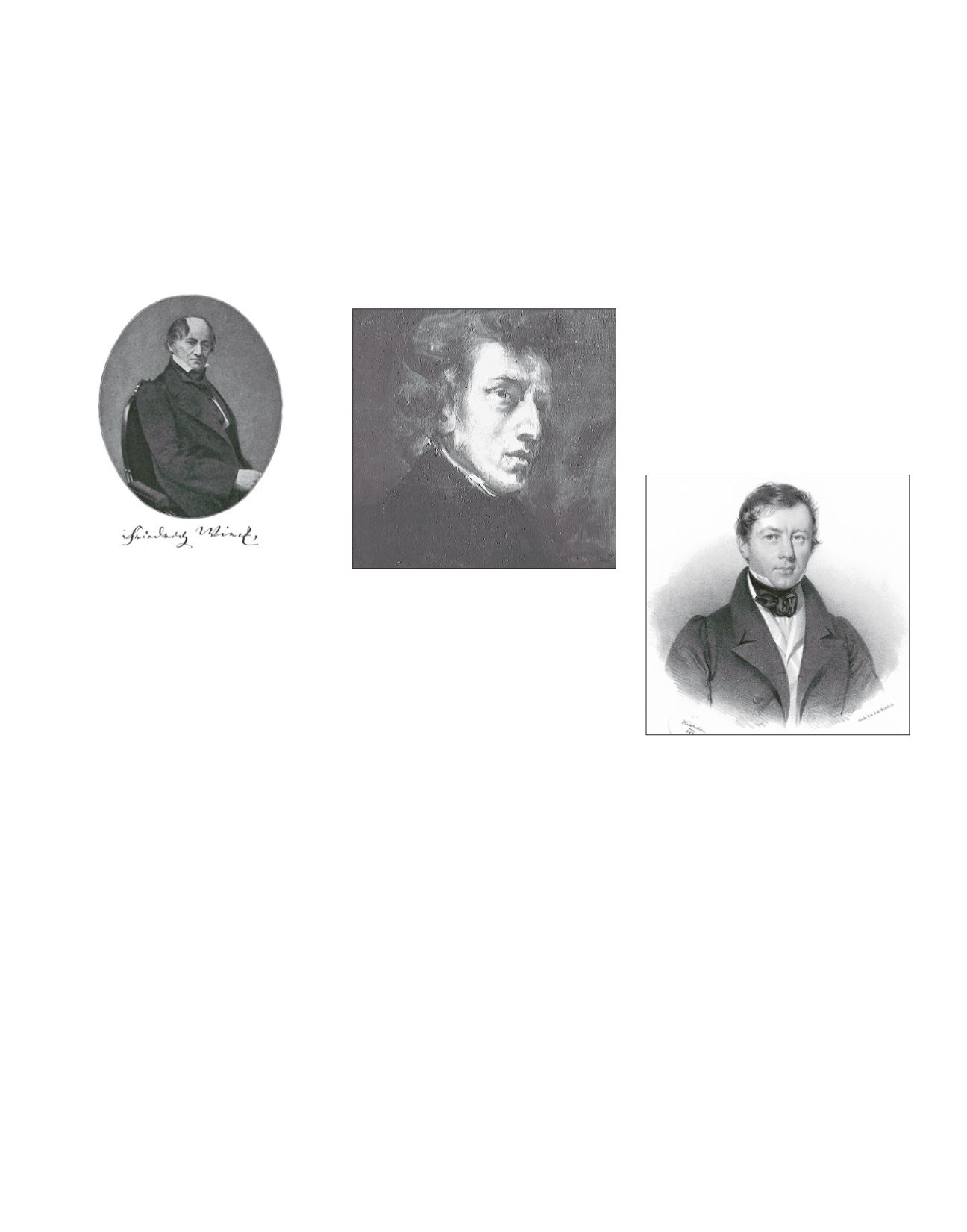

Friedrich Wieck

Lithograph of Tobias Haslinger by Joseph Kriehuber

(1842)

Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin by Eugène Delacroix

RAVINIA MAGAZINE | AUGUST 27 – SEPTEMBER 2, 2018

102