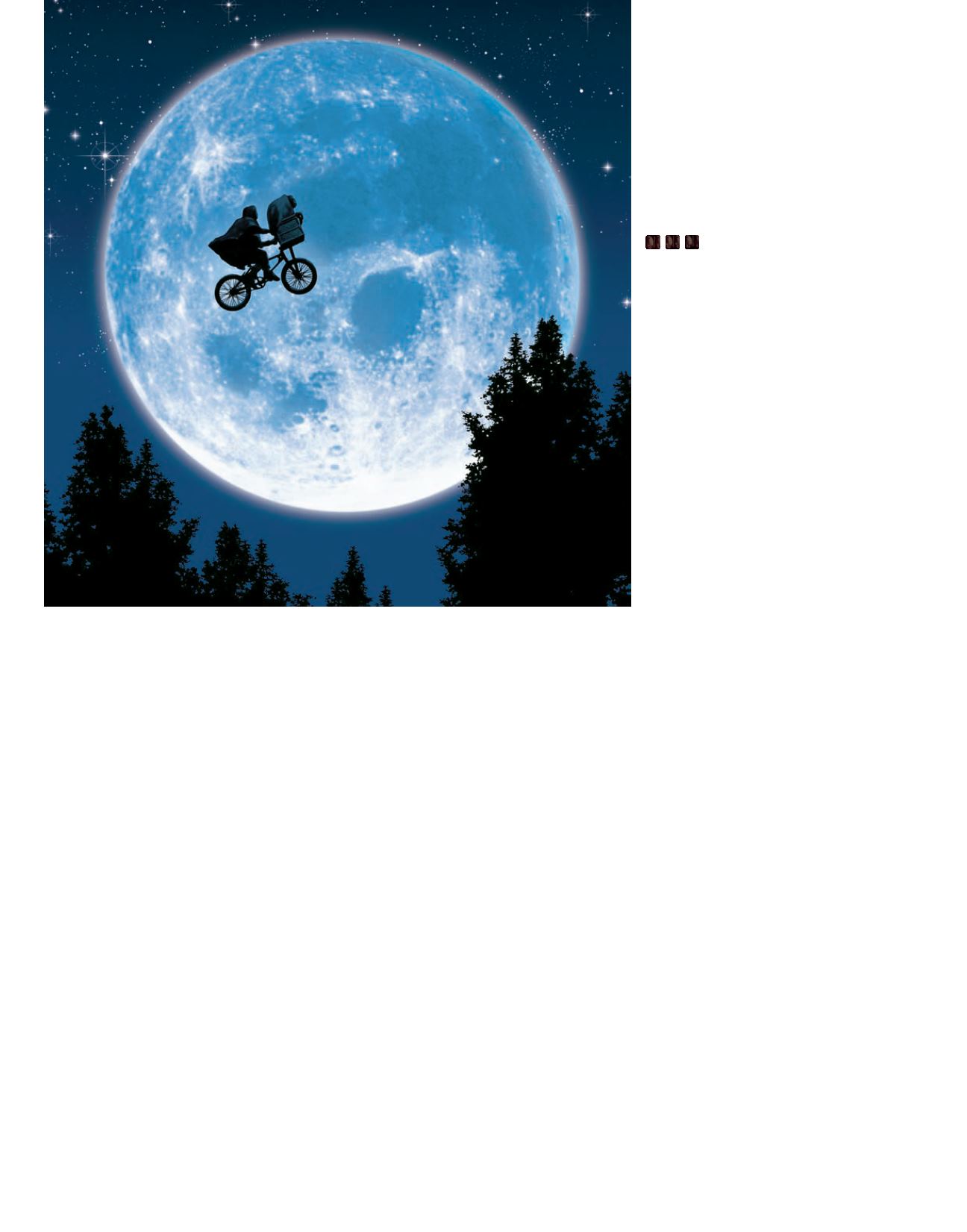

( 7 PDNLQJ (OOLRWWȅV ELNH ɷ\ RYHU WUHHV DJDLQVW WKH EDFNGURS RI WKH PRRQ ZDV VXFK D FDSWLYDWLQJ PRPHQW

that not only does Williams cite it as one of his favorite scenes melding his music with Spielberg’s visuals, the

director also uses it as the logo for his production company, Amblin Entertainment, which was founded the year

before

E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial

hit theaters.

omas) takes a nocturnal ight with

the adorable alien on his bicycle. “I love

it for its sweetness and sense of inno-

cence,” he said, “and absence of gravity.”

Spielberg selected the elaborately

staged chase/action scene from

Raiders

where a wounded Indiana Jones (Park

Ridge, IL, native Harrison Ford) inven-

tively uses his whip to thwart Nazis.

“ ere’s a musical progression,” he said,

“an amazing, accelerated ostinato where

Johnny actually tells you when to really

get excited. I love the percussion. I love

the horns. Once again, I can close my

eyes and not need the visuals to feel like

I’m on a journey to save the Lost Ark of

the Covenant.”

e theme to

Raiders

ranks as one of

Williams’s most iconic works. Spielberg

credits its success to the composer’s

sense of timing and restraint. “He

sparingly uses it,” Spielberg elaborated.

“When he uses it, it allows us to root for

the hero. When he doesn’t use it, we are

worried about our hero. He’s so wise as

to when to release the main theme.”

When creating his movie music mag-

ic, Williams eschews computers. He uses

pencils, paper, and a piano. Sometimes,

Spielberg quietly pays a visit to the

composer and hints for a status report.

“If I feel like I’ve got something for him,

I’ll play a few notes,” Williams said. “I

can always tell by his eyes, his facial

expression, his voice, if he’s unsure, if he

dislikes it, or likes it. e great thing is

that he always leaves happy.”

Williams rarely reads screenplays,

although he did read

Close Encounters

of the ird Kind

to synchronize the

score with the alien spacecra ’s musical

exchange. Surprisingly, he doesn’t watch

movies much. “I didn’t go [to movies] as

a child,” he confessed. “I had radio.”

Williams turned in February, and

Spielberg turned in December. How

do they keep their partnership fresh?

“He [Williams] makes the promise,”

Spielberg said, “and it’s my job to keep

the promise. en if I can’t, then it’s his

job to write better music than I directed,

so he can keep the promise for me.

“ at’s kind of how it’s been working

for the past years or so.”

Gee, this could qualify as the longest

“showmance” in Hollywood history.

OTHER FAMOUS COMPOSER/DIRECTOR

TEAMS

have conducted themselves into

cinematic forces similar to the Williams/

Spielberg and Herrmann/Hitchcock

duos, and doubtlessly more will contin-

ue to surface and one day receive the

mantle of “greatest today.” Despite the

year-in–year-out ubiquity of certain

names under the line “Music by,” an

examination of these ear/eye-catching

combos reveals how democratic the

job of scoring lms can be, with the

musicians’ origins varying from concert

pianists to pop or rock band singers.

Ennio Morricone/Sergio Leone, lms.

Although Italian composer Ennio Mor-

ricone paired with other directors more

times than with Sergio Leone, American

audiences are most familiar with them

primarily for their collaboration on

Clint Eastwood’s “Man With No Name”

spaghetti western trilogy, beginning

with

A Fistful of Dollars

in

. e mi-

serly music budget did not allow for an

orchestra, forcing Morricone to impro-

vise by inserting bells and whip cracks

into the score. Morricone also bucked

western movie tradition by boldly using

anachronistic electric guitars, one of

the xtures in the composer’s iconic

masterpiece for

e Good, the Bad, and

the Ugly

with its stunning, operatic track

“ e Ecstasy of Gold.”

Nino Rota/Federico Fellini, lms

(plus a TV movie and a documentary).

A child prodigy who composed an ora-

torio at age (and published his works

at ), Nino Rota became best known

in America for his romantic theme to

Franco Ze erelli’s

Romeo and Juliet

and

highly romanticized theme to Francis

Ford Coppola’s

e Godfather

. But his

simple, memorably melodic works

(more than

scores) will be forever

tied to the lms of the great Federico

© & ™ UNIVERSAL STUDIOS

RAVINIA MAGAZINE | JULY 23 – AUGUST 5, 2018

24