much going on, my music re ects the chaos.”

Growing up, the natural inner turmoil of adolescence was

magni ed exponentially by the turmoil experienced by his

family and his country. at was also re ected in his early

attempts at playing music, Kuti observes: “As a young man

growing up, I was very anxious and angry. … Learning the

trumpet, I became frustrated because I thought it was going to

be an easy task. It was very di cult. But the end result was, it

made me a better person, cooler, wiser.”

e instruments he chooses to best express his muse are

trumpet and saxophone, although he also dabbles in piano—

“very badly,” he says with a chuckle, “to nd the chords, to get

the bass line or the melody. e piano is a major factor of my

compositions. Well, I probably start them o while sleeping, in

a dream, waking up to a melody. ose are fantastic tunes.”

Kuti brings a new perspective to his signature sounds on

One People One World

—liberally adding tracks about inspi-

ration and love to his signature political anthems. e album

kicks o with “Africa Will Be Great Again,” hits a high point

with the title track, and winds down with an Afrobeat take on a

ballad, “ e Way Our Lives Go (Rise and Shine).”

“ is has to do with my age, where I am right now with

my life,” Kuti says. “ ‘ e Way Our Lives Go,’ it re ects a very

quiet area. So maybe I was on tour [when I rst started com-

posing it], somewhere very quiet, and this music re ects my

subconscious.

“As a father,” he continues, “I have to be optimistic in many

things I do. I have to give them hope. I think I’m very happy

where I am right now. I’m at peace with many things around

me, so that’s re ected in this album.”

Family was very much on his mind during the months

or so he spent working on

One People One World

, because his

eldest son, Omorinmade—Mad

é

for short—joined the band in

the recording studio. ( ey’ve also played live shows together,

not just in Lagos but recently in London and Paris.) It’s an

obvious generational mirror, because Femi played with Fela’s

band; but also Mad

é

is following in his grandfather’s footsteps

by studying music at England’s Trinity College of Music.

Kuti, the father of nine children

(six biological and three adopted), says

the experience of making music with

-year-old Madé was “fantastic, one of

the most beautiful things. … I think he’s

a better person than I am, and he’s going

to be a better musician than I am. Noth-

ing he’ll do will really surprise me. e

way he walked into the studio, the way

he takes his school life seriously, the way

he relates to issues—at his age, I wasn’t

doing all of this.”

Kuti was at home in Lagos during his

interview with

Ravinia

Magazine, so the

conversation naturally turned to how he

approaches performing in Chicago ver-

sus performing in Lagos, where he’s of-

ten heard at his home club, e Shrine.

(It was established by Kuti and his older

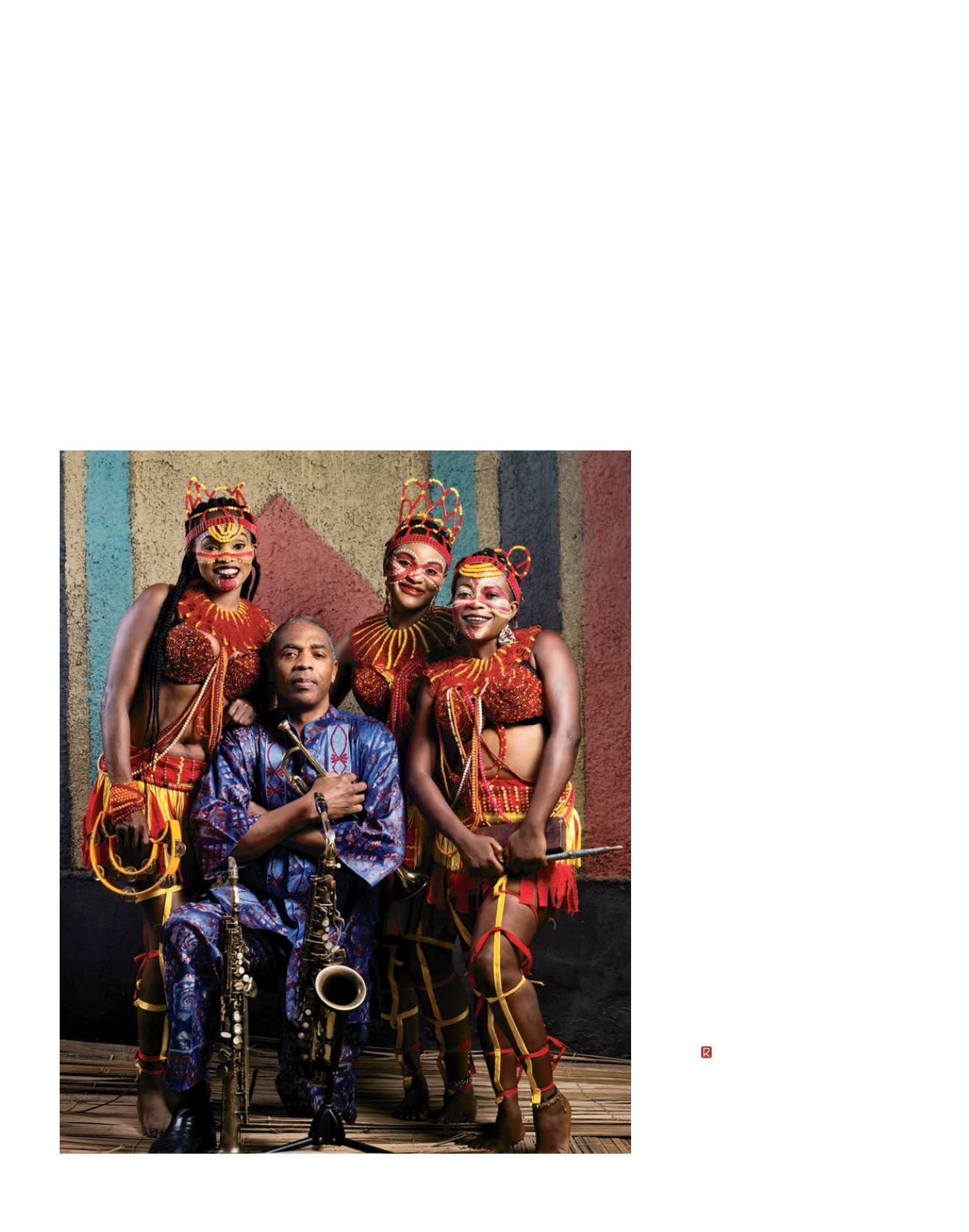

sister in memory of their father.) “First

of all, my priority is to show the beauty

of Africa. at is my rst rule,” says the

informal cultural ambassador. “I will say

this before the gig: I want them to see

the beauty of Africa through music, so

I get them in a trance. I just want them

to see Africa in its true light. I use the

colored costumes, the music, the sound,

and everything to express the pain, the

sorrow, and the joy we have. And I hope

that they will experience this though the

music.”

Web Behrens covers arts, culture, and travel for the

Chicago Tribune

and

Crain’s Chicago Business

.

He’s also worked as an editor and contributor for

Time Out Chicago

and the

Chicago Reader

.

RAVINIA MAGAZINE | AUGUST 6 – AUGUST 19, 2018

20