conducted by the young Arturo Toscanini. The response was decidedly

tepid. Such a flaccid reaction seems mind-boggling today. Perhaps

Puccini’s music seemed a trifle dull, lacking both the pyrotechnical

dazzle of the old repertory or the primal intensity of the new –

particularly in the absence of a real

aria d’urlo

, a feature of verismo in

which a character veers from lyricism and essentially begins to scream

(though we have a suggestion of that from Rodolfo at Mimì’s death).

In any case, this was not a matter of audience favor overriding critical

dissent (Puccini would experience that later with

Tosca

). This time

around, the audience wasn’t crazy about it either.

Bohème

’s ascension

was to be fueled by its interpreters.

Chief among these was the great Australian diva Nellie Melba.

Dame Nellie was a huge star, both at the Met and particularly at

Covent Garden, where she ruled with an iron fist. She was also a

soprano in search of new material. Melba had built her reputation in

such florid Italian roles

—

most prominently Donizetti's Lucia

—

and

was also celebrated as Gounod's Juliet and Marguerite. Audience tastes

had changed, however. Melba’s outing as Nedda in

Pagliacci

was well

received, but an ill-advised attempt at Brünnhilde in Wagner’s

Siegfried

was a disaster. “I have been a fool,” Melba told the press, in a rare

moment of humility. In truth, Melba was anything but. She knew she

needed to evolve, and that the excesses of verismo were a poor fit for

her vocally and temperamentally. But Puccini’s Mimì was something

else. Here was a modern role that would allow her to exploit her

preternaturally beautiful timbre and exquisitely floated upper tones.

Melba plunged into six weeks of study in the role with Puccini himself.

The composer declared her an ideal Mimì (an assessment informed,

no doubt, by his awareness of Melba’s considerable influence with

management – Puccini was no fool, either).

Melba aggressively campaigned for Covent Garden to mount

Bohème

for her, which they did in 1899, despite their distaste for

the “new and plebeian opera.” Her performance created a sensation.

Soprano Mary Garden left a revealing account of Melba’s achievement,

specifically the floated high C concluding “O soave fanciulla.” “The

note came floating over the auditorium of Covent Garden; it left

Melba's throat, it left Melba's body, it left everything, and came over

like a star and passed us in our box, and went out into the infinite. I

have never heard anything like it in my life, not from any other singer,

ever. My God, how beautiful it was! That note of Melba's was just like

a ball of light.” The Met capitulated as well, and Melba became their

first Mimì in 1900, with the unusual caveat that she sing the mad scene

from

Lucia di Lammermoor

following the opera, as a panacea for those

who remained skeptical.

Then there was Caruso. If there ever was a perfect match of

composer and voice, it was Giacomo Puccini and Enrico Caruso.

Caruso’s extraordinary tenor instrument, with its ringing, honeyed

sweetness on top and surprising complement of beef in the middle

register, was ideally served by Puccini’s music. It could have been

written for him, and Caruso knew it. His appearances as Rodolfo

opposite Melba at Covent Garden in 1902 caused pandemonium. The

press also had a field day with an extra-musical event that occurred. As

legend has it, Caruso, a notorious practical joker, pressed a hot sausage

into Melba’s hand as he sang “Che gelida manina” (“Your little hand is

frozen”). It was a juicy little story, and it kept the singers – and

Bohème

– firmly in the public consciousness.

O P E R A N O T E S | L Y R I C O P E R A O F C H I C A G O

October 6 - 20, 2018

|

31

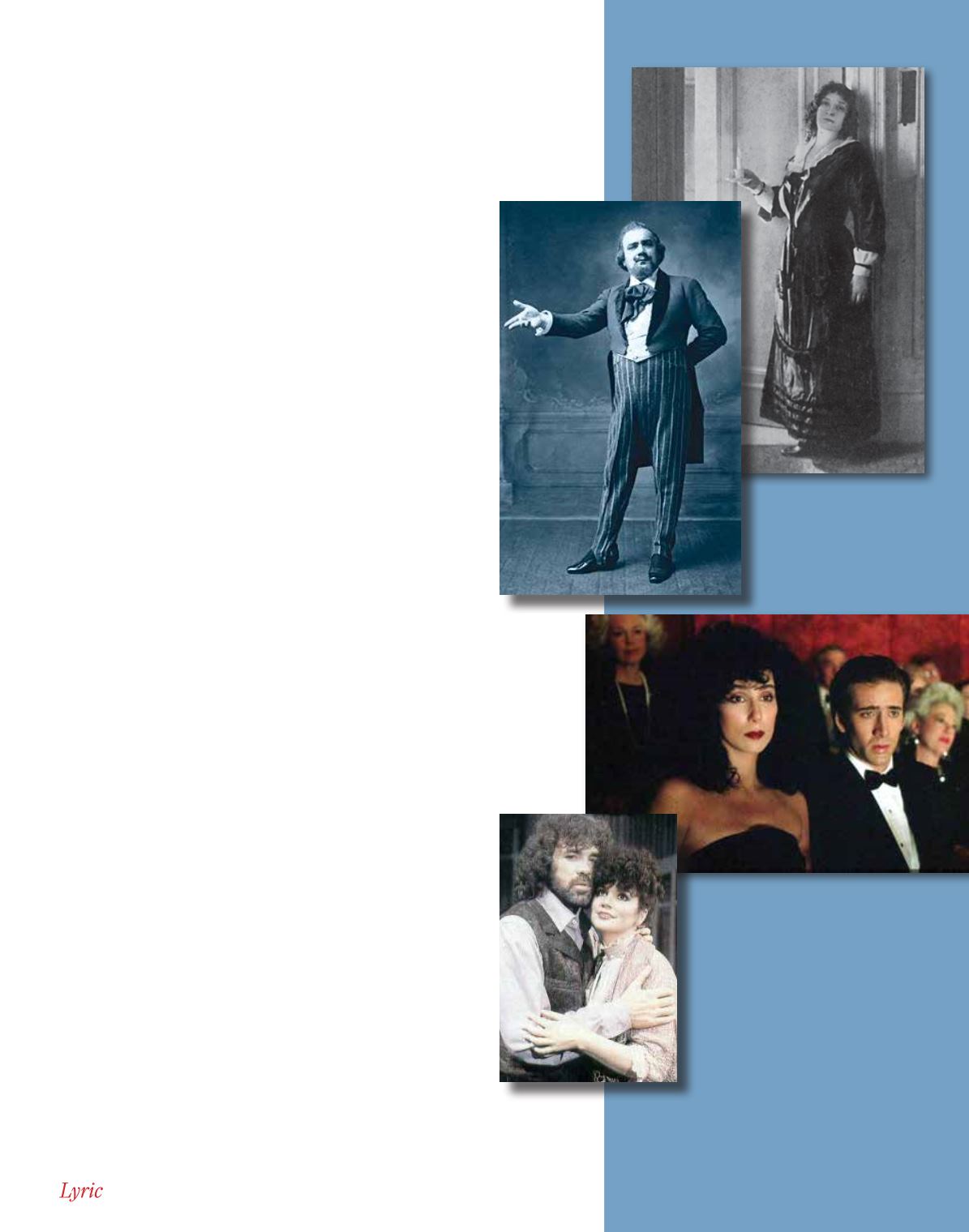

Pictured as Rodolfo

and Mimi are the two

legendary singers who

did the most to bring

La

bohème

to world attention

– Enrico Caruso and

Dame Nellie Melba.

(Above) Nearly a century after

the heyday of Melba and Caruso,

La bohème

was essential to one of

the most successful films of the 1980s,

Moonstruck

. In a crucial scene,

Loretta (Cher) attends a Metropolitan

Opera performance of

Bohème

with

opera-loving Ronny (Nicolas Cage),

her fiancé’s brother, who’s fallen in

love with her.

Singing in English, country singer Gary Morris played

Rodolfo and Linda Ronstadt was Mimì in the New

York Shakespeare Theater’s 1984 English-language

production of

La bohème

.

METROPOLITAN OPERA ARCHIVES