marches for the countess) instead of the

Con

delicatezza

of the final version. Furthermore,

Schubert struggled with the work’s closing sec-

tion. The composer and Franz Lachner gave the

first performance on May 9, 1828.

The Fantasy in F minor, D. 940, represents

Schubert’s most grandiose creation for four-

hands piano. Its music essentially outlines a tra-

ditional four-movement cycle, though without

breaks between movements. The opening sec-

tion amounts to a sonata-like movement com-

posed around a fanfare figure and a more lyrical

melody in F minor/major. After a grandiose

gesture, the

Largo

settles into an Italianate mel-

ody. The

Allegro vivace

and the

Con delicatezza

form a

scherzo

–

trio

–

scherzo

grouping. Schubert

concludes the Fantasy with contrapuntal elabo-

rations on his opening themes.

AARON COPLAND (1900–90)

El Salón México

(arranged for two pianos by Leonard Bernstein)

“Mexico offers something fresh and pure and

wholesome—a quality which is deeply uncon-

ventionalized. The source of it is the Indian

blood, which is so prevalent. I sensed the influ-

ence of the Indian background everywhere—

even in the landscape. And I must be something

of an Indian myself, or how else explain the sym-

pathetic chord it awakens in me,” wrote Copland

following his first trip south of the US border.

The congeniality of Mexico completely absorbed

Copland during his five-month visit in 1932/33.

The conductor Carlos Chávez introduced him

to many local attractions in and around Mexi-

co City. While strolling through the streets one

evening, they entered a nightclub called El Salón

México, where Copland first experienced the

bewitching charm of native Mexican music.

These haunting melodies and spirited rhythms

fascinated Copland, who soon began an orches-

tral work, entitled

El Salón México

, which incor-

porates actual folk melodies in a type of “modi-

fied potpourri.” Chávez conducted the Orquésta

Sinfónica de México in the world premiere on

August 27, 1937. Ironically, this “Mexican” com-

position became one of the most popular pieces

by Copland, the “dean of American composers.”

Boosey & Hawkes, hoping to capitalize on the

success of

El Salón México

, commissioned ar-

rangements for solo piano and for two pianos.

Copland recommended a promising young mu-

sician who “was also badly in need of money

and would therefore do the job for a really mis-

erable fee”—Leonard Bernstein.

MAURICE RAVEL (1875–1937)

La valse

Ravel first contemplated a tribute to Johann

Strauss Jr. in 1906, as he explained to music

critic Jean Marnold: “It is not subtle—what I

am undertaking at the moment. It is a

grande

valse

, a sort of

hommage

to the memory of the

Great Strauss, not Richard, the other—Johann.

You know my intense sympathy for this admi-

rable rhythm and that I hold

la joie de vivre

as

expressed by the dance in far higher esteem than

as expressed by the Franckist puritanism.” The

anticipated composition assumed the working

title

Wien

(Vienna).

Many events distracted him from this project,

but none more tragic than the political and

personal developments of the 1910s—wartime

rationing, his mother’s death, and compulsory

military service. Far removed from Paris after

the war, Ravel recuperated in the rural sur-

roundings of Lapras. Perhaps nostalgia drove

him finally to produce his Strauss waltz in two

versions, for solo and duo pianos (1919). Ravel

and Alfredo Casella introduced this piece at Vi-

enna’s Kleiner Konzerthaussaal on October 23,

1920. Two months later, the orchestral version

received its world premiere in Paris.

La valse

(subtitled

Poème choréographique

), like

the Strauss family waltzes, actually consists of

several waltz themes. Ravel outlined his music

in a preface to the orchestral score: “Through

openings in the whirling clouds, couples of

waltzers may be seen. Little by little the clouds

disperse, and one is able to distinguish an im-

mense room peopled with a crowd turning

round and round. Gradually the scene brightens

and the light of the chandeliers blazes out. An

imperial court around 1855.”

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1872–1915)

Two Études

Many who knew Alexander Scriabin considered

him an insufferable egomaniac and an eccentric

who espoused the mystical theosophy of Ma-

dame Blavatsky and who associated pitches with

specific colors. Before earning that questionable

reputation, Scriabin made a more positive mark

on Russian musical life as a talented young pia-

nist. He joined the studio of Nikolai Zverev, a re-

nowned pedagogue whose other pupils includ-

ed Serge Rachmaninoff and Alexander Siloti, at

age 12. Four years of advanced keyboard train-

ing prepared him for admission to the Moscow

Conservatory, where his musical studies also

included theory, fugue, and composition. Scri-

abin graduated with the “little” gold prize for pi-

ano—finishing behind Rachmaninoff—in 1892

and embarked on a performing career.

The piano remained the principal medium for

his constantly evolving musical expression.

In general terms, Scriabin’s style blended lush

Chopinesque harmonies and counterpoint with

Lisztian virtuosity and experimentation with

keyboard sonority. His choice of composition-

al types (nocturnes, mazurkas, impromptus,

preludes, polonaises, nocturnes, and études)

demonstrates a particularly close affinity for

Chopin. Three of Scriabin’s études—op. 2, no. 1

(1887), op. 49, no. 1 (1905), and op. 56, no. 4

(1907)—are isolated within potpourri keyboard

collections. The majority of his studies belong

to three sets completed at nine-year intervals:

op. 8 (1894) contains a dozen pieces arranged

into two groups of six, eight more appeared in

op. 42 (1903), and the remaining three form

op. 65 (1912).

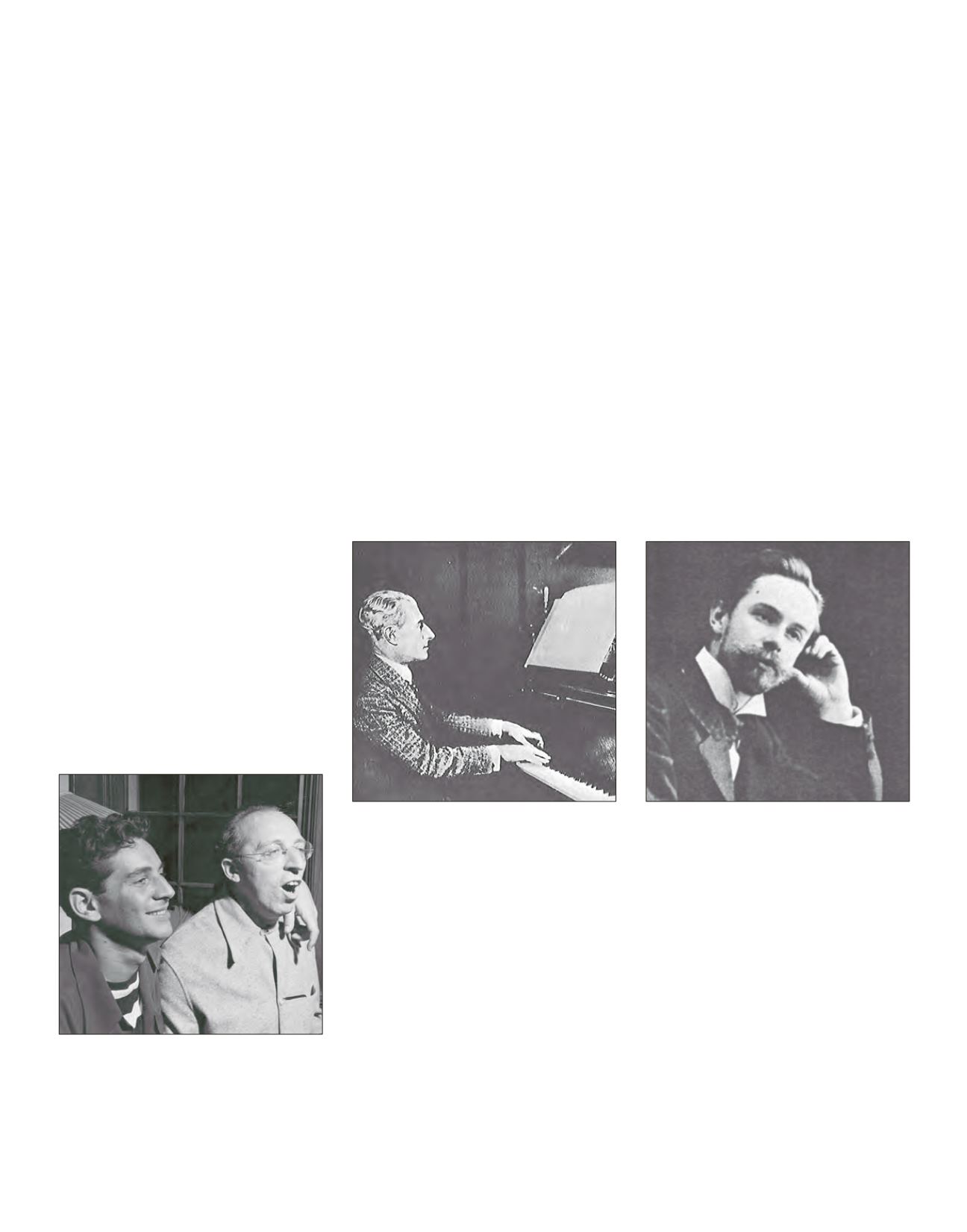

Leonard Bernstein and Aaron Copland

Maurice Ravel

Alexander Scriabin

JULY 23 – JULY 29, 2018 | RAVINIA MAGAZINE

99