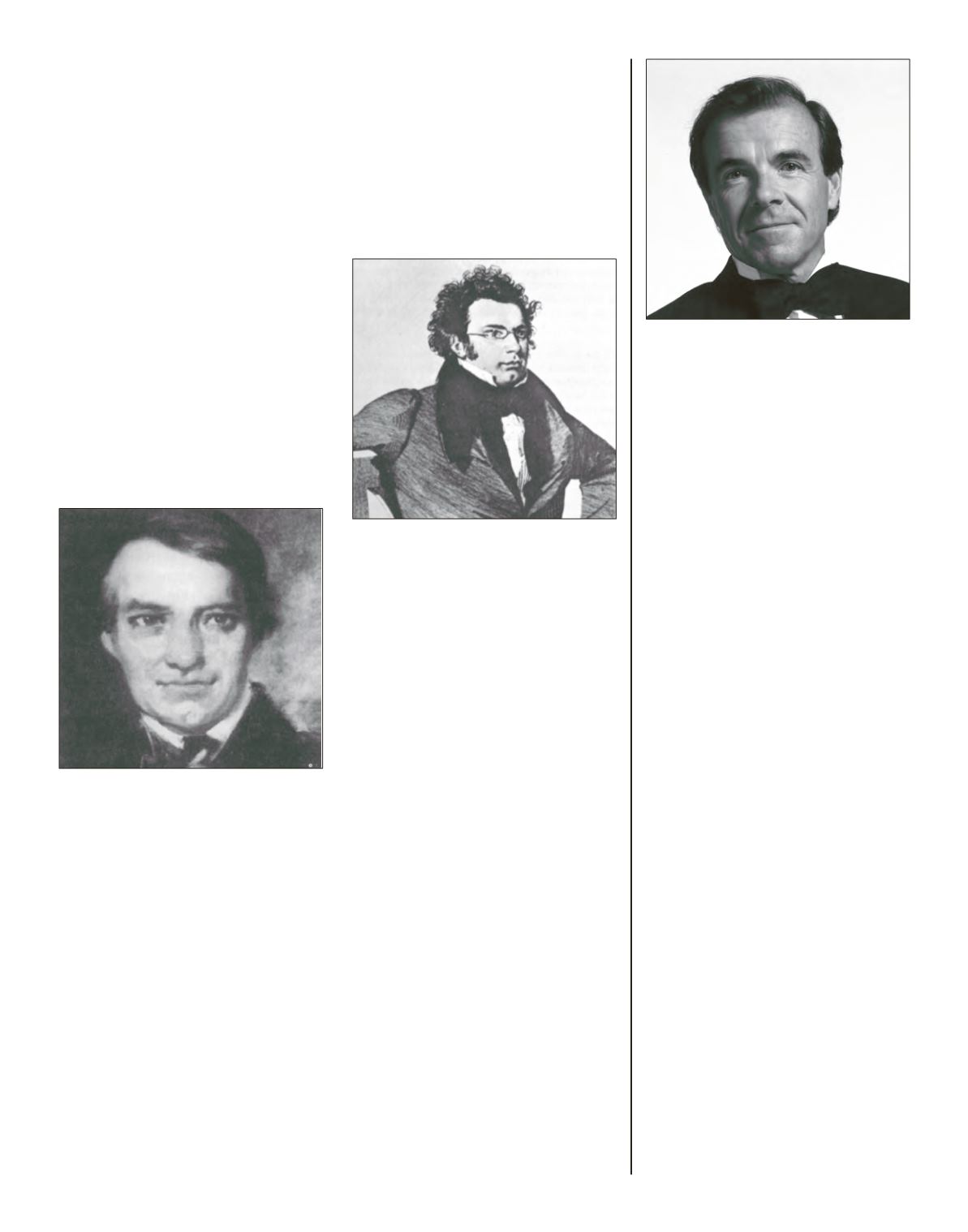

FRANZ SCHUBERT

Piano Sonata in A major, D. 959

By the summer of 1828, Schubert’s financial situ-

ation reached a point of desperation, prompting

him to accept lodging in his brother Ferdinand’s

house, cancel a vacation in Graz, and compro-

mise his professional integrity. Just around the

corner lurked grave complications from his de-

clining physical condition. Negotiations with

foreign publishers reflected his urgent need for

income. In a last-ditch appeal, Schubert offered

Leipzig publisher H.A. Probst several “proven

successes.”

“I amwriting to inquire when the trio is going to

be published. … I am looking forward to publi-

cation with great longing. I have also composed

three sonatas for pianoforte, which I propose

dedicating to [pianist Johann Nepomuk] Hum-

mel. Moreover, I have set to music several songs

of Heine from Hamburg, which met with great

approval here. And, finally, I have composed a

quintet for two violins, one viola, and two vi-

oloncellos. I have played the sonatas at several

places and always with success.”

Realizing the composer’s dire straits, Probst

shrewdly bought the trio for one-quarter of the

asking price. Schubert reaped no benefits from

the three piano sonatas (D. 958–960), which he

introduced at a private gathering of friends on

September 27, 1828, at the home of Dr. Ignaz

Menz. Six weeks later, Schubert died at the age

of 31. Anton Diabelli first published these sona-

tas posthumously in 1839 as the composer’s “fi-

nal works.” Robert Schumann, who guided these

pieces into print, received the dedication.

Beethoven’s legacy exerts itself on the sheer

magnitude of these four-movement sonatas,

although their breadth results from a charac-

teristically Schubertian melodic profusion. In

the Piano Sonata in A major, D. 959, Schubert

carefully disguises the “thematic” nature of

his bold opening

Allegro

chords; lyrical ideas

emerge several measures later. However, the

MISHA DICHTER,

piano

Misha Dichter was born in Shanghai in 1945—

his Polish parents having fled Europe at the out-

break of World War II—and grew up in Los An-

geles, where he began piano lessons at age 6. In

addition to his concentrated studies of the key-

board in the German Classical style with Aube

Tzerko, a pupil of Artur Schnabel, Dichter also

delved into the Russian Romantic tradition un-

der the tutelage of Rosina Lhevinne at Juilliard.

While still a student, at age 20 he won Moscow’s

Tchaikovsky Competition with repertoire re-

flecting these dual influences— Schubert and

Beethoven, Rachmaninoff and Stravinsky—cat-

apulting him into an international performing

career. Within two years Dichter had performed

Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 with both

Erich Leinsdorf and the Boston Symphony Or-

chestra at Tanglewood (broadcast live on NBC)

and Leonard Bernstein and the New York Phil-

harmonic, and appearances with such leading

European ensembles as the Berlin Philhar-

monic, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, and

the principal London orchestras, as well as the

other top American orchestras, soon followed.

His discography is as diverse as his musical in-

terests, including the complete piano concertos

of Brahms with Kurt Masur and the Leipzig

Gewandhaus Orchestra and of Liszt with An-

dré Previn and the Pittsburgh Symphony Or-

chestra, plus Gershwin’s

Rhapsody in Blue

with

Neville Marriner and the Philharmonia Orches-

tra, as well as Brahms’s solo works, Beethoven’s

piano sonatas, Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies,

and music by Chopin, Mussorgsky, Schubert,

Schumann, Stravinsky, and Tchaikovsky. He

won the Grand Prix International du Disque

Liszt in 1998 for his album of the composer’s pi-

ano transcriptions. In addition to regularly col-

laborating with his wife, Cipa, on piano duo re-

citals, Misha frequently works with many of the

world’s finest string ensembles and holds master

classes at such conservatories and universities

as Juilliard, Curtis, Eastman, Yale, and Harvard.

Tonight marks Misha Dichter’s 47th season at

Ravinia, where he first performed in 1968.

recapitulation makes this introduction’s the-

matic importance clear by placing these chords

at the most dramatic point. Greater melodic

and harmonic simplicity typifies the secondary

theme. The development creates a sense of for-

ward motion with frequent modulations, rather

than thematic fragmentation or compression.

Schubert restores both themes to melodic com-

pleteness, extending the second idea through a

type of delayed development. A coda contains

quiet reminders of the opening chords.

The

Andantino

combines the rocking berceuse

rhythms in the left hand with a soulful, folk-like

melody. Several writers have observed that this

movement’s character and piano figuration re-

semble Schubert’s song

Pilgerweise

, D. 789. This

all changes with the fantasy wanderings of the

middle portion, which climaxes in a dramatic

exchange of loud chordal exclamations and in-

trospective, single-line phrases. An embellished

version of the opening theme concludes the

movement.

Extreme dynamic and mood changes animate

the

Scherzo

. However, its central section retreats

to pianistic gentility and elegant hand-cross-

ing. The finale is a relatively understated essay

in rondo form. Origins of its refrain melody

trace back to the slow movement of Schubert’s

Piano Sonata in A minor, D. 537 (1817). Melodic

variety comes in the form of a simple, repeat-

ed-note melody and a developmental section.

An incomplete and fragmented refrain leads to

the

presto

coda.

–Program notes © 2018 Todd E. Sullivan

Ferdinand Schubert

Franz Schubert

RAVINIA MAGAZINE | JULY 23 – JULY 29, 2018

100