characters—the Bride, her Bridegroom, the

Preacher, and a Pioneer Woman—quietly enter

onto the stage. Presumably, Graham conceived

the loving young couple to idealistically por-

tray her recent marriage. In fact, Graham and

Hawkins danced the leading roles, while Merce

Cunningham portrayed the Preacher and May

O’Donnell the Pioneer Woman.

Graham modeled the Pioneer Woman on her

great grandmother, a resourceful woman who

moved from Virginia to the rich soils of Penn-

sylvania during the previous century. “She terri-

fied me. She was very beautiful and was always

very still. What her father did, and what was

passed down in family lore, was wear his best

Sunday shirt to do his farming in the belief in

the nobility of physical labor. And before he

did any work, she had to be sure to iron it each

morning.”

Several dances ensue: a vivacious fiddler’s dance,

the tender

pas de deux

for the Bride and Bride-

groom, a fast group dance with the Preacher and

his congregation, and a solo by the Bride. Next

follows the deservedly famous variations on the

Shaker melody “Simple Gifts.” Copland remem-

bered finding this tune in a 1940 collection. He

understood that “the dance would have been in

a lively tempo, with a single file of brethren and

sisters two and three abreast proceeding with

utmost precision around the meeting room. In

the center of the room would be a small group

singing the dance song over and over until ev-

eryone was both exhilarated and exhausted. Lest

this seem very scholarly, my research evidently

was not very thorough, since I did not realize

that there never have been Shaker settlements in

rural Pennsylvania.”

Fragments of earlier themes return, climaxing in

the final version of “Simple Gifts.” As the young

couple enter their new house and begin a life to-

gether, tender strains of the introductory music

return with an ambiguous sense of excitement

and hope, yet uncertainty over what mysteries

lie ahead.

Graham left her ballet untitled—although Cop-

land had operated with the working title

Ballet

for Martha

—until the day before the premiere

on October 30, 1944, at the Coolidge Festival

in Washington, DC. Her choice of

Appalachian

Spring

was derived from a line in Hart Crane’s

poem “The Bridge.” She explained to the com-

poser: “It really has nothing to do with the bal-

let. I just liked it.” Copland solidified his “Amer-

ican” style in

Appalachian Spring

. Aside from

the Shaker tune, no actual folk material appears

within the score. However, Copland evoked the

folk spirit in his mildly dissonant, yet captivat-

ingly simplistic musical material. Both choreog-

rapher Graham and set designer Isamo Noguchi

conformed their ideas to this uncluttered, direct

expression.

Appalachian Spring

earned the New

York Music Critics Circle Award as the out-

standing theatrical work of the 1944–45 season,

and Copland’s score garnered the Pulitzer Prize

in Music for 1945.

GEORGE GERSHWIN (1898–1937)

Rhapsody in Blue

Scored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets

and one bass clarinet, two bassoons, three horns,

three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani,

crash cymbals, suspended cymbal, gong, snare and

bass drums, triangle, bells, two alto and one tenor

saxophones, banjo, strings, and solo piano

Paul Whiteman announced a provocative con-

cert in the

New York Tribune

on January 4, 1924.

The stated purpose of this musical event was to

decide “What is American music?” According

to the four-paragraph article, Whiteman had

assembled a distinguished panel of musicians

to decide the question. Among other music,

the program would contain three new compo-

sitions: a jazz concerto by George Gershwin, a

“syncopated tone poem” by Irving Berlin, and

an American suite by Victor Herbert.

Ira Gershwin brought this article to his broth-

er’s attention. George apparently had forgotten

about the “jazz concerto” project, which he had

discussed only in vague terms with Whiteman.

With less than six weeks before the concert, the

surprised musician began mapping out ideas.

Gershwin’s account of the creative process ap-

peared in 1938, one year after his tragic death

from brain cancer: “I had no set plan, no struc-

ture to which my music must conform. The

Rhapsody

, you see, began as a purpose, not as

a plan.” Sometime before January 7, Gershwin

had combed his “tune books” for useful melodic

ideas. Shuttling between New York and Boston

for the tryout of his musical

The Perfect Lady

(produced on Broadway as

Sweet Little Devil

),

Gershwin’s imagination came alive to the sounds

of his passenger train “with its steely rhythms,

its rattlety-bang. … I suddenly heard—even

saw on paper—the complete construction of the

Rhapsody

from beginning to end.”

AARON COPLAND (1900–90)

Appalachian Spring

: Ballet for Martha

Scored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets,

two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, and two

trombones, timpani, xylophone, snare and bass

drums, cymbals, tabor (long drum), wood block,

claves, glockenspiel, triangle, harp, piano, and strings

Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge—one of America’s

foremost patrons of the arts—first attended

a performance by dancer and choreographer

Martha Graham during the early 1940s. Gra-

ham’s striking modern technique impressed

Coolidge, who soon commissioned three new

ballets for her foundation’s annual fall festival at

the Library of Congress. For these productions,

Coolidge also commissioned musical scores

from Aaron Copland (

Appalachian Spring

),

Darius Milhaud (

Jeux de printemps

, or

Imag-

ined Wing

), and Carlos Chávez. Paul Hindemith

eventually took over Chávez’s commission and

produced the ballet

Mirror before Me

, later re-

named

Hérodiade

.

Several years earlier, Graham had based her

dance

Dithyramb

on Copland’s Piano Varia-

tions. However, the Coolidge commission af-

forded these two seminal American artists their

first opportunity to collaborate start-to-finish

on a ballet production. Graham initially submit-

ted a brief dramatic script to Copland, who was

composing film scores in Hollywood at the time.

The original scenario involved several American

aspects, including a young Native American girl

modeled on Pocahontas. Graham had devel-

oped a fascination with Native American life,

dance, and ritual on a trip to the Southwest fol-

lowing her marriage to Erick Hawkins, the lead-

ing male dancer in her company. Although Na-

tive American elements ultimately disappeared

from the story line, Graham retained one sty-

listic influence in her production—the “squash

blossom hair arrangement” of the Hopi women.

The ballet scenario gradually evolved into

wedding celebrations in a 19th-century Penn-

sylvania farming community. Four principal

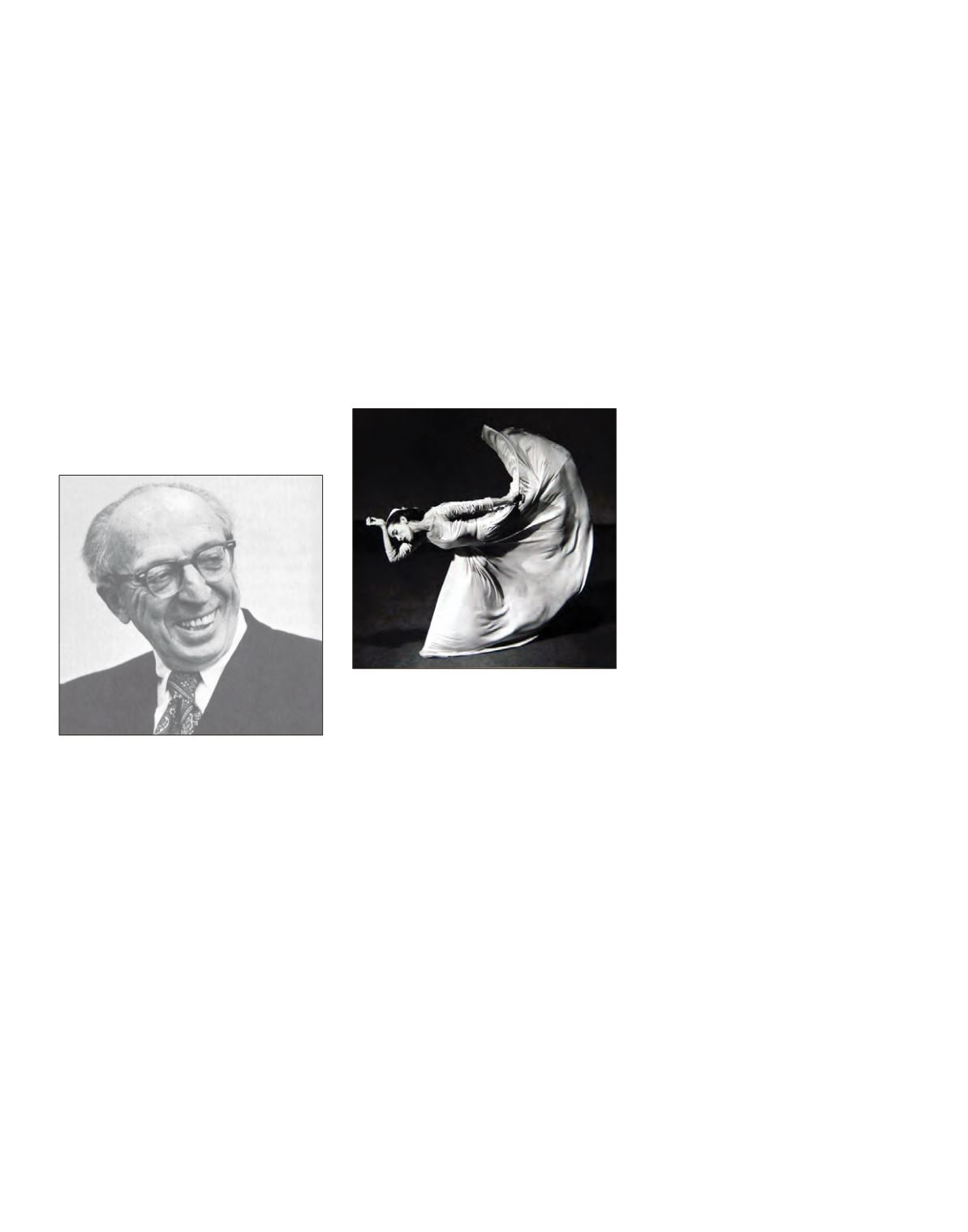

Martha Graham

Aaron Copland

RAVINIA MAGAZINE | JULY 23 – JULY 29, 2018

106