golden shovel used for the Lincoln Memorial

and Jefferson Memorial, on December 2, 1964.

By mid-1966, Bernstein had received two invita-

tions from Jacqueline Kennedy connected to the

emerging cultural center. The composer-con-

ductor initially agreed to serve as the center’s

artistic director, but later declined the position.

However, Bernstein gladly accepted Mrs. Ken-

nedy’s commission for a new composition to

celebrate the opening of the center: “the highest

honor I have ever been accorded.” Conducting

engagements had ruthlessly limited his time for

composition; Bernstein had produced only two

major compositions over the previous decade

since

West Side Story

: Symphony No. 3 (

Kad-

dish

) and the

Chichester Psalms

.

Construction delays pushed the Kennedy Cen-

ter opening beyond the scheduled 1969 date.

Meanwhile, Bernstein had begun envisioning

a large-scale theatrical setting of the Mass—in

honor of the Kennedys, who were Catholic—

that confronted current issues in a contem-

porary style. This approach mirrored recent

changes in the Catholic Church, instituted by

the Second Vatican Council (1962–65), that

emphasized ecumenical dialogue, vernacular

languages in worship, and popular styles of li-

turgical music and art.

Seemingly with time to spare before the opening,

Bernstein turned his attention to other projects.

Immediately he flew to Los Angeles to oversee

a revival of

Candide

at Royce Hall. His second

collection of essays,

The Infinite Variety of Music

,

was published in August 1966. Two months later,

Bernstein announced plans to retire as music di-

rector of the New York Philharmonic at the end

of his current contract (1969), when he would

receive the lifetime title of Laureate Conductor.

His guest conducting engagements, most nota-

bly with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra and

Vienna Philharmonic, increased.

One project that consumed much of Bernstein’s

time was a film directed by Franco Zeffirelli,

who had turned his attention to religious sub-

jects after the successes of two recent Shake-

speare films,

The Taming of the Shrew

(1967) and

Romeo and Juliet

(1968). Zeffirelli and Bernstein

labored for three months on a portrayal of the

life of Saint Francis of Assisi. When creative dif-

ferences drove Bernstein and his lyricist, Leon-

ard Cohen, from the project, Zeffirelli turned to

Italian film composer Riziero (“Riz”) Ortolani

and pop singer-songwriter Donovan to write

the

Brother Sun, Sister Moon

(1972) soundtrack.

Bernstein did not leave the project empty-hand-

ed. Two remnants eventually made their way

into

Mass

: the well-known “Simple Song” heard

in the

Devotion before Mass

and a quatrain by

Paul Simon (“Half of the people are stoned”),

which emerged as a Trope in the

Gloria

. Any

disappointment Bernstein suffered from the

collapse of the Saint Francis project quickly dis-

sipated amid work on a musical theater adap-

tation of Bertolt Brecht’s

The Caucasian Chalk

Circle

, which also fizzled after two months.

The new opening date for the Kennedy Cen-

ter—September 8, 1971—crept closer. Though

Bernstein’s concept for

Mass

had come into

focus, actual composition lagged far behind

schedule. Back in New York after conducting

the New York Philharmonic on a tour of Japan

and the southern United States in August and

June 1970, Bernstein learned that his Kennedy

Center colleague Roger L. Stevens had suffered

a heart attack. While visiting the hospital, Bern-

stein asked what he could do for his convalesc-

ing friend. “Lenny, one thing I’d like to have you

do for me is finish

Mass

,” Stevens replied. This

was the incentive Bernstein needed to quicken

his work.

In December, Bernstein retreated to the Mac-

Dowell Colony in Peterborough, NH, for artis-

tic inspiration and concentrated work on

Mass

.

There, a large portion of its music was assem-

bled from existing material or was newly com-

posed. Engagements with the Vienna Philhar-

monic—live filming of Mahler symphonies and

a European tour—occupied February through

May. Back in the US, Bernstein resumed his

frenzied work on

Mass

, refining references to

Christian ritual and political resistance, devel-

oping English lyrics to match the Latin liturgical

text, and imposing order and coherence on the

overall dramatic structure.

His consultations with antiwar activist Catholic

priests Father Daniel Berrigan and Father Phil-

ip Berrigan, who was imprisoned in the Fed-

eral Correctional Institution at Danbury along

with six others (the “Harrisburg Seven”) for

allegedly plotting to kidnap National Security

Advisor Henry Kissinger, caught the attention

of President Richard Nixon and the FBI under

J. Edgar Hoover. Based on information from an

unknown prison informant, the FBI issued two

memos on “Proposed Plans of Antiwar Elements

to Embarrass the United States Government.”

Bernstein’s forthcoming

Mass

stood at the cen-

ter of this imagined conspiracy. In the second

memo (August 16, 1971), R.L. Shackelford wrote

to C.D. Brennan “To advise that information re-

garding a previously reported plot by Leonard

Bernstein, conductor and composer, to embar-

rass the President and other government offi-

cials through an antiwar and anti-Government

musical composition to be played at the dedica-

tion of the Kennedy Center for the Performing

Arts has been reported by the press.” The memo

stated that, based on this information, President

Nixon had decided not to attend the Kennedy

Center opening “in order to minimize the ef-

fectiveness of Bernstein’s plot to embarrass the

administration.”

Bernstein still had not identified a collabora-

tor to write the English lyrics by June, leaving

the composer “terribly depressed,” according

to his sister Shirley. (Stephen Sondheim, who

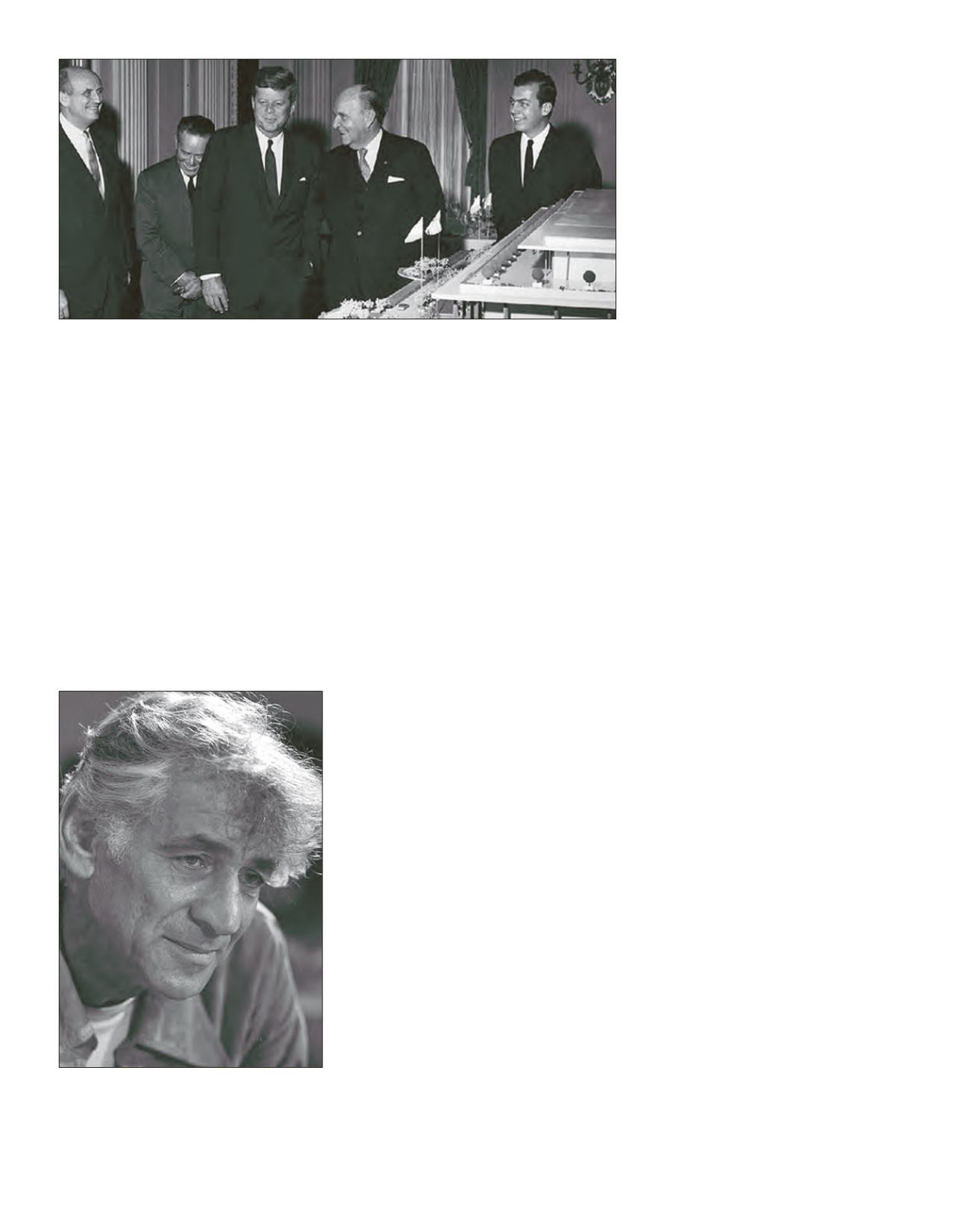

Leonard Bernstein (1971)

President John F. Kennedy with architect Edward Durell Stone (to his left) and the model of the National Cultural

Center that would later bear his name

JULY 23 – JULY 29, 2018 | RAVINIA MAGAZINE

121