had so successfully partnered with Bernstein

on

West Side Story

, turned down the oppor-

tunity.) Drawing on her connections as a the-

atrical agent, Shirley suggested a 23-year-old

composer-lyricist currently enjoying his first

off-Broadway success with

Godspell

, a musical

theater adaptation of the Gospel according to

Saint Matthew—Stephen Schwartz. Shirley took

her reluctant brother to the

Godspell

produc-

tion, and Lenny subsequently talked through

his

Mass

concept with Schwartz. “Oh my God,

this is it,” Lenny reported to Shirley. “Now I can

finish

Mass

.”

After two weeks of blazing work together, Ber-

nstein and Schwartz had essentially completed

Mass

. The seasoned composer outlined the var-

ied themes in

Mass

—a memorial for President

Kennedy, a reflection of the unrest within so-

ciety and organized religion, loss of individual

faith, and hope for collective peace—and the

younger librettist translated those intentions

into contemporary language and a clear dra-

matic organization. “What happened was the

entire work, from a lyric point of view, is first

draft,” Schwartz recalled. “As soon as a piece was

completed to some sort of satisfactory end, we

moved on. And there really was not the time to

go back and improve the work.” Decades later, a

more mature wordsmith no longer working un-

der the extreme press of time, Schwartz revised

his

Mass

lyrics without changing a note of Bern-

stein’s music. The Bernstein Estate accepted the

majority of these new lyrics, which premiered in

an August 19, 2004, performance at the Holly-

wood Bowl.

The final month before the premiere brought an

avalanche of activity. In early August, Bernstein

oversaw production of the quadraphonic re-

cordings, heard throughout the score, in CBS’s

high-tech recording studios in New York City.

Hershy Kay and Jonathan Tunick were selected

to provide orchestrations. Tom Cothran—the

former music director at KKHI, a now-defunct

AM classical music radio station in San Fran-

cisco, and Bernstein’s new personal assistant—

thoroughly proofread the score and oversaw the

frantic last-minute copying of parts in a Wash-

ington, DC, hotel room.

As the subtitle explains,

Mass

is not a liturgical

work but “a theater piece for singers, players, and

dancers,” a musical theater composition based

on a ritual model. Bernstein produced his most

musically ecumenical score, a kaleidoscope of

classical, jazz, rock, musical theater, folk, and

gospel styles, in a work that confronted grandi-

ose, almost universal human conditions, much

as his admired Gustav Mahler had done decades

before. “I feel it’s a work I have been writing

my entire life,” Bernstein once confessed. The

original production of

Mass

required a large

production team: Gordon Davidson (director),

Alvin Ailey (choreographer), Oliver Smith (set

design), Frank Thompson (costumes), Gilbert

Hemsley Jr. (lighting), Maurice Peress (conduc-

tor), Roger L. Stevens (producer), and Schuler

G. Chapin (associate producer). The cast in-

cluded Alan Titus (the Celebrant), the Norman

Scribner Choir, Berkshire Boys’ Choir, Alvin

Ailey American Dance Theatre, and instrumen-

talists. The premiere took place on September 8,

1971, with members of the Kennedy family in

attendance. President Kennedy’s widow, Jac-

queline, who by that time had married Aristotle

Onassis, was conspicuously absent.

Bernstein’s decision to compose a work entitled

Mass

, the most central musical statement in

Christian observance, provoked much contro-

versy. Even Peress, a former assistant conductor

for Bernstein at the New York Philharmonic,

questioned, “What’s a Jewish boy like you doing

writing a mass?” This monumental score was

Bernstein’s musical exercise in questioning au-

thority, examining personal integrity, and—as

in the case of his Symphony No.

3 (

Kaddish

),

written eight years earlier—struggling bitterly

with matters of faith. The Celebrant, whom Per-

ess described as suffering a midlife crisis, bears

more than a passing resemblance to the 53-year-

old composer-conductor-pianist. The choice of

Christian subject matter stirred enough hullaba-

loo, but Bernstein ignited a veritable firestorm

with his approach to dramatizing the venerable

Latin text. The Celebrant’s crisis of faith during

Fraction

: “Things Get Broken,” when he hurls

the sacrament to the floor, produced the loudest

cries of sacrilege. As in

Kaddish

, faith is affirmed

at the end after a tortured spiritual voyage.

I.

Devotion before Mass

.

Pre-recorded voices

enter sequentially, pleading for mercy (“Kyrie

eleison”) to a highly chromatic melody. Their

cacophonous chorus builds “to a point of max-

imum confusion,” when a spotlight focuses on

a young man in blue jeans and basic shirt—the

Celebrant—who sings “A Simple Song” of praise

to his own guitar accompaniment. The pre-re-

corded voices respond by scat-singing “Alleluia.”

II.

First Introit

(Rondo).

The exultation spills

onto the stage as a marching band leads the

Street Chorus and Children’s Choir to the altar

of God. The Celebrant pronounces the liturgical

salutation, “Dominus vobiscum” (“God be with

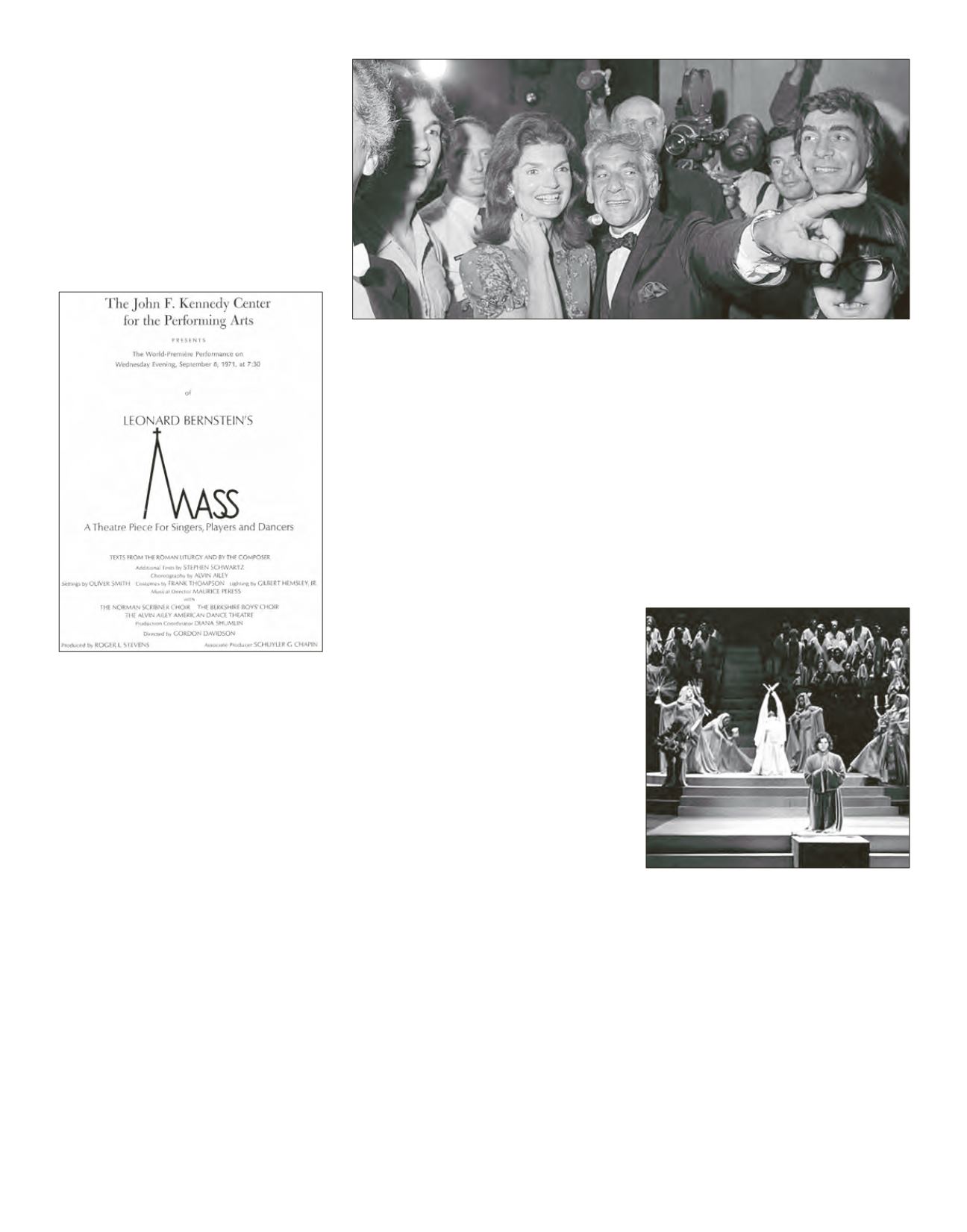

Program cover for the premiere of Bernstein’s

Mass

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis tours the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts with Leonard Bernstein

(1972)

Scene from the premiere of Bernstein’s

Mass

RAVINIA MAGAZINE | JULY 23 – JULY 29, 2018

122