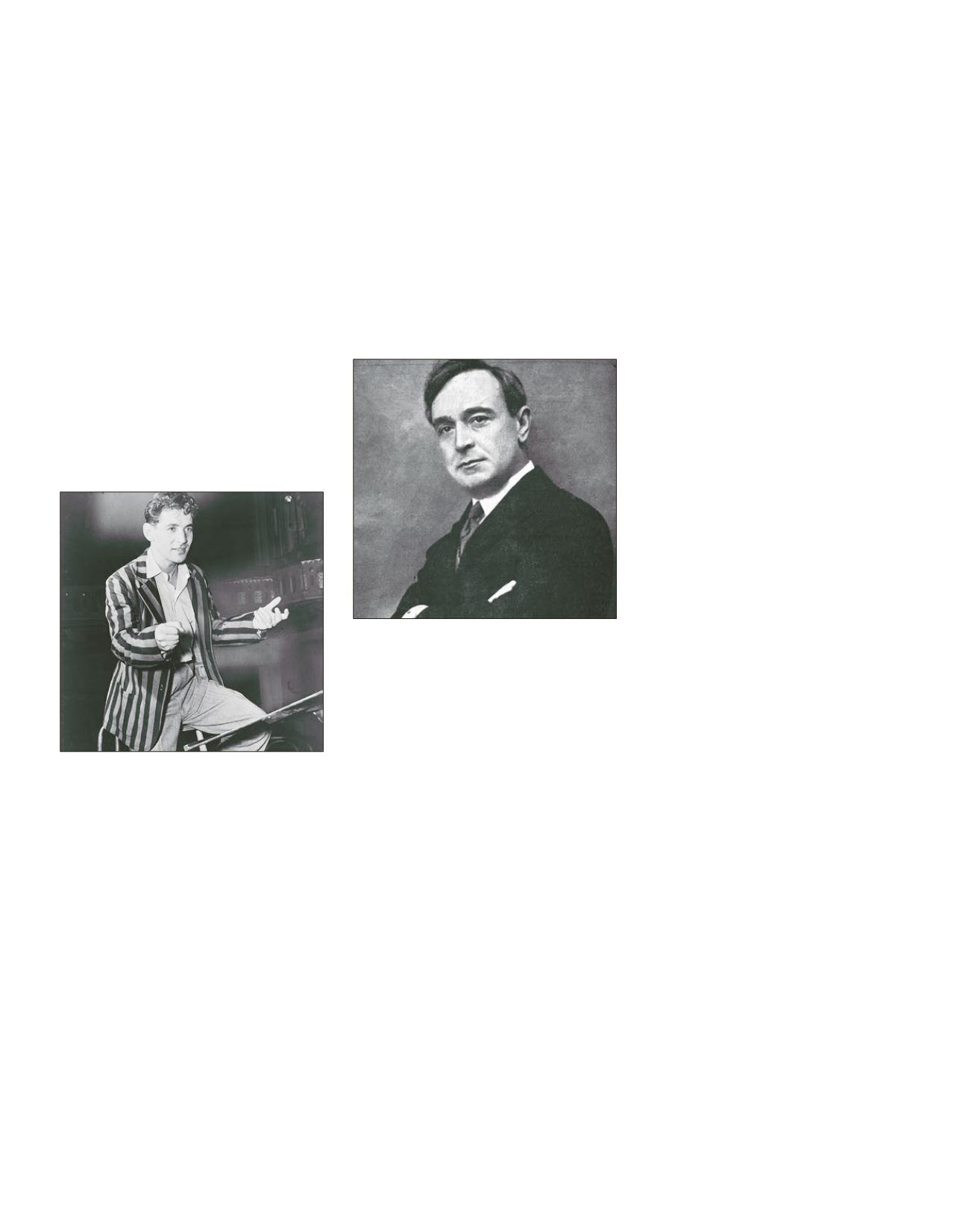

LEONARD BERNSTEIN (1918–90)

Symphony No. (“Jeremiah”)

Scored for two utes and piccolo, two oboes and En-

glish horn, two clarinets and bass clarinet, two bas-

soons and contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets,

three trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, bass drum,

snare drum, suspended cymbal, crash cymbals, wood

block, piano, strings, and mezzo-soprano soloist

Leonard Bernstein was still a relatively unknown

musician—an assistant to Russian conductor

Serge Koussevitzky at Tanglewood, a part-time

music copyist (under the pseudonym Lenny

Amber; “Bernstein” is German for “amber”), pi-

ano accompanist and soloist, and an occasional

jazz club performer—when he composed the

“Jeremiah” Symphony in

.

e young mu-

sician had heard of a composition competition

sponsored by the New England Conservatory.

His mentor Koussevitzky was chairman of the

jury, and Bernstein felt reasonably optimistic

about his chances at winning. Unfortunately, the

December submission deadline was literally

days away.

Brimming with energy, Bernstein sketched the

rst movement and a scherzo for his rst sym-

phony in days. Running short on time, he

transformed his earlier

Lamentation

for soprano

and orchestra ( ) into the nale of the new-

ly conceived “Jeremiah” Symphony. Bernstein

reassigned the vocal part to a mezzo-soprano.

With preliminary material for three movements

complete, he began the arduous task of orches-

trating the music.

ree days remained before the deadline; an

almost impossibly short period of time. Shirley

Bernstein, who joined her brother in New York,

described the nal ordeal: “A small army of

friends and I were put to work helping to get the

mechanical part of the job done. I was kept busy

inking in clefs and time signatures, two friends

[composer David Diamond and clarinetist Da-

vid Oppenheim] took turns making ink copies

of the already completed orchestration, anoth-

er checked the copies for accuracy, and Lenny’s

current girlfriend [Edys Merrill] kept us all sup-

plied with co ee to keep us awake on this -

hour friend-in-need task.”

is rag-tag team miraculously completed the

score, although too near the deadline to mail

the manuscript. Lenny boarded a train to Bos-

ton with Edys, who personally hand-delivered

the manuscript to Koussevitzky’s residence two

hours before midnight on New Year’s Eve.

e

exhausted composer returned to New York and

slept for nearly a week. Despite this heroic col-

lective e ort, Bernstein failed to win the prize.

Koussevitzky later admitted an unfavorable

opinion of this composition by his protégé. Ber-

nstein shelved the “Jeremiah” Symphony for the

next two years.

In the meantime, he had made a now-legend-

ary ascent onto the conductor’s podium. Artur

Rodziński, the newly installed music director

of the New York Philharmonic, summoned

the young man in August

to his summer

residence, White Goat Farm, with an entic-

ing proposal: the assistant conductor position

with the orchestra. Bernstein later fostered an

embellished version of their meeting in which

Rodziński allegedly stated, “I have gone through

all the conductors I know of in my mind, and

I nally asked God whom I should take, and

God said, ‘Take Bernstein.’ ” Further, Bernstein

insisted that Rodzinski made his o er on Au-

gust —Lenny’s th birthday.

Arthur Judson, the founding head of Columbia

Artist Management, contracted Bernstein with-

in a month and mounted a media blitz. Before

long, major media in the United States contact-

ed this American wunderkind for interviews.

His growing celebrity hit high gear with his New

York Philharmonic debut on November ,

,

as a last-minute substitute for the ailing Bruno

Walter. A normally surly press corps hailed his

dynamic performance.

e Bernstein legend

was born.

Orchestras across the country rushed to secure

Bernstein as a guest conductor. Fritz Reiner,

music director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Or-

chestra and Bernstein’s conducting instructor

at the Curtis Institute of Music, was among the

rst in line. Reiner enticed his former student

with the opportunity of conducting his dormant

“Jeremiah” Symphony, and Bernstein agreed to a

date in January

. Rodziński attempted to re-

call his popular assistant to New York, but Ber-

nstein honored the commitment to Pittsburgh,

leading the premiere with mezzo-soprano Jen-

nie Tourel on January .

Critical reaction to the symphony was consider-

ably less unanimous than to his conducting de-

but. Warren Story Smith published an extremely

positive review in the

Boston Post

: “To quote

Schumann’s famous salutation to Chopin: ‘Hats

o , gentlemen, a genius!’ ”

e irascible Virgil

omson, on the other hand, wrote more crit-

ically of Bernstein’s compositional technique.

Nonetheless, the “Jeremiah” Symphony received

the Music Critics’ Circle Award for

.

Bernstein once commented, “ e work I have

been writing all my life is about the struggle

that is born of the crisis of our century, a crisis

of faith.”

is spiritual preoccupation is easily

explainable because of two potent in uences on

the composer: his father Samuel, a successful

businessman and the son of a Hasidic scholar

(also the dedicatee of the symphony), and the

composer Gustav Mahler, whose own sym-

phonies probed spiritual issues. For Bernstein,

“ e faith or peace that is found at the end of

‘Jeremiah’ is really more a kind of comfort, not

a solution. Comfort is one way of achieving

peace, but it does not achieve the sense of a new

beginning.”

e composer acknowledged only a modest

debt to Hebrew music in his symphony, but

Bernstein’s personal assistant Jack Gottlieb has

traced direct, though perhaps unconscious,

echoes of several Hebrew chants.

e opening

theme in

Prophecy

is derived from two liturgi-

cal cadences: a traditional Amen sung during

the

ree Festivals of Passover, Shavuot (Feast

of Weeks), and Sukkot (Festival of Tabernacles),

and another cadence used during the Amidah

prayers in the High Holy Days. Bernstein ex-

plained that this tormented movement “aims

only to parallel in feeling the intensity of the

prophet’s pleas with his people.”

Profanation

is the symphony’s scherzo, designed

“to give a general sense of the destruction and

chaos brought on by the pagan corruption with-

in the priesthood and the people.” Bernstein dis-

played his ingenious sense of orchestral color, an

attribute praised by Virgil omson, and trade-

mark rhythmic verve in this dance-inspired

movement. Gottlieb discovered a formula used

during the chanting of the Bible, speci cally the

Ha ara (conclusion) on Shabbat (the Sabbath).

e revised

Lamentation

concludes the sympho-

ny with an agonizing vocal essay that Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein (1945)

Serge Koussevitzky (photograph by Boris Lipnitzky)

AUGUST 13 – AUGUST 19, 2018 | RAVINIA MAGAZINE

107