e exertion of this prolonged creativity took its

toll on Ravel. A er nishing the Piano Concer-

to for the Le Hand, he escaped to the Basque

region to regain strength before completing the

Piano Concerto in G major. Symptoms of the

mysterious neural illness that impaired his abil-

ity to compose and ultimately brought his death

in

—Pick’s disease—had already begun to

surface. Ravel grew nervous as the scheduled

premiere of his Piano Concerto in G major ap-

proached. He determined with good, but sadly

prophetic, humor, “I can’t manage to nish my

concerto, so I’m resolved not to sleep for more

than a second. When my work is nished I shall

rest in this world … or the next!”

e concer-

to was nally completed in

. Ravel decided

against performing the new work himself, in-

stead o ering the premiere (and subsequent Eu-

ropean tour performances) to Marguerite Long,

who gave the premiere on January ,

, with

the composer conducting the Lamoureaux Or-

chestra. Unknowingly, Ravel had created his last

orchestral work.

e opening

Allegramente

of the Piano Con-

certo in G major reveals an exceedingly eclectic

style. A startling snap launches the movement

on its rhythmically propulsive path, under-

scored by the piano guration. Ravel begins

with a Basque-styled theme, perhaps a remnant

of the abandoned piano concerto

Zaspiak-Bat

,

whose music was developed into a piano trio. A

trumpet assumes this melody, giving it a Cop-

landesque coloration.

e rst piano solo wa-

vers between jazz in uences and the composer’s

own “impressionist” language. A high-lying bas-

soon melody and trumpet response accentuate

the jazz legacy.

Ravel heard numerous popular American mu-

sical idioms during his US sojourn, but he

was most impressed with the potential of jazz

and blues. He expressed genuine interest and

support for the further development of these

styles during a speech before students at Rice

University (April ,

): “My journey is en-

abling me to become still more conversant with

those elements which are contributions to the

gradual formation of a veritable school of Amer-

ican music. … May this national American mu-

sic of yours embody a great deal of the rich and

diverting rhythm of your jazz, a great deal of the

emotional expression in your blues, and a great

deal of the sentiment and spirit characteristic of

your popular melodies and songs, worthily de-

riving from, and in turn contributing to, a noble

heritage of music.”

Ravel rst heard George Gershwin’s music in

New York while attending Broadway perfor-

mances of

Funny Face

in

. When asked what

he wanted as a birthday present, Ravel replied

“to hear and meet George Gershwin.” Formal

introductions were made the following year by

a mutual friend, the singer Eva Gauthier. Gersh-

win’s piano playing astounded the Frenchman.

Gauthier wrote, “George that night surpassed

himself, achieving astounding feats in rhythmic

intricacies so that even Ravel was dumbfound-

ed.” When Gershwin traveled to Paris in

, he

asked to study composition with Ravel, only to

receive a complimentary refusal: “Why should

you become a second-rate Ravel when you can

be a rst-rate Gershwin?” e in uence of Ger-

shwin’s piano playing (including distinct echoes

of the

Rhapsody in Blue

) is strongly felt in Ravel’s

Piano Concerto in G major.

Ravel’s rst movement continues along the

lines of a traditional sonata form. Cadenzas for

harp—playing sonorous glissandos and a mel-

ody in harmonics—and the woodwind section

break up the development. A solo-piano caden-

za prefaces the melodically rich recapitulation.

e

Adagio assai

, a movement of exquisite beau-

ty, o ers pure Ravelian lyricism. e solo piano

introduction establishes an atmosphere of mys-

tical simplicity belied by the con icting rhyth-

mic patterns in the le and right hands ( / and

/ , respectively). Strings and woodwinds enter

with greatest delicacy, adding melodic phrases

above the piano accompaniment.

e piano

leads into a central section devoted to harmonic

wandering and an elaborately embellished treble

part. ese gurations gain rhythmic impulse as

the original melody reappears in the soulful En-

glish horn.

Ravel returns to the “divertimento” ideal in his

Presto

nale, a sort of sonata-rondo. Rapid pi-

ano gures combine with clarinet, trombone,

piccolo, and trumpet wails.

is primitivistic

music recalls Stravinsky’s

Petrushka

ballet score.

Clarinets and piano engage in a supple exchange

of ideas. Horns and trumpets add a march-like

theme.

e movement drives excitedly to its

conclusion.

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–75)

Symphony No. in D minor, op.

Scored for two utes and piccolo, two oboes, three

clarinets, two bassoons and contrabassoon, four

horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba,

timpani, snare drum, triangle, cymbals, bass drum,

tam-tam, bells, xylophone, two harps, celesta, piano,

and strings

An urgent message came over the

New York

Times

wire in

from Soviet correspondent

Harold Denny: “

. Dmitri Shostakovich, who

fell from grace two years ago, on the way to re-

habilitation. His new symphony hailed. Audi-

ence cheers as Leningrad Philharmonic presents

work.” Although Aram Khachaturian’s Piano

Concerto also received its premiere on that

November concert at the Festival of Soviet

Music, which celebrated the th anniversary of

the October Revolution, it was Dmitri Shosta-

kovich’s Symphony No. that brought the au-

dience to its feet.

e diminutive, bespectacled

composer walked onstage dozens of times to

acknowledge the thunderous ovation. One audi-

ence member, A.N. Glumov, recalled conductor

Yevgeny Mravinsky’s grandiose, sel ess gesture:

“[He] li ed the score high above his head, so as

to show that it was not he, the conductor, or the

orchestra who deserved this storm of applause,

these shouts of ‘bravo’; the success belonged to

the creator of this work.”

e Symphony No. o ered more than “reha-

bilitation”: it was a glorious resurrection for the

recently beleaguered Shostakovich. His troubles

began on January ,

, when

Pravda

printed

an aggressive attack against his latest (and pop-

ularly acclaimed) opera

Lady Macbeth of the Mt-

sensk District

. Titled “Muddle instead of Music,”

this article condemned the “Le ist confusion

instead of natural, human music.

e power of

good music to infect the masses has been sac-

ri ced to a petty-bourgeois, Formalist attempt

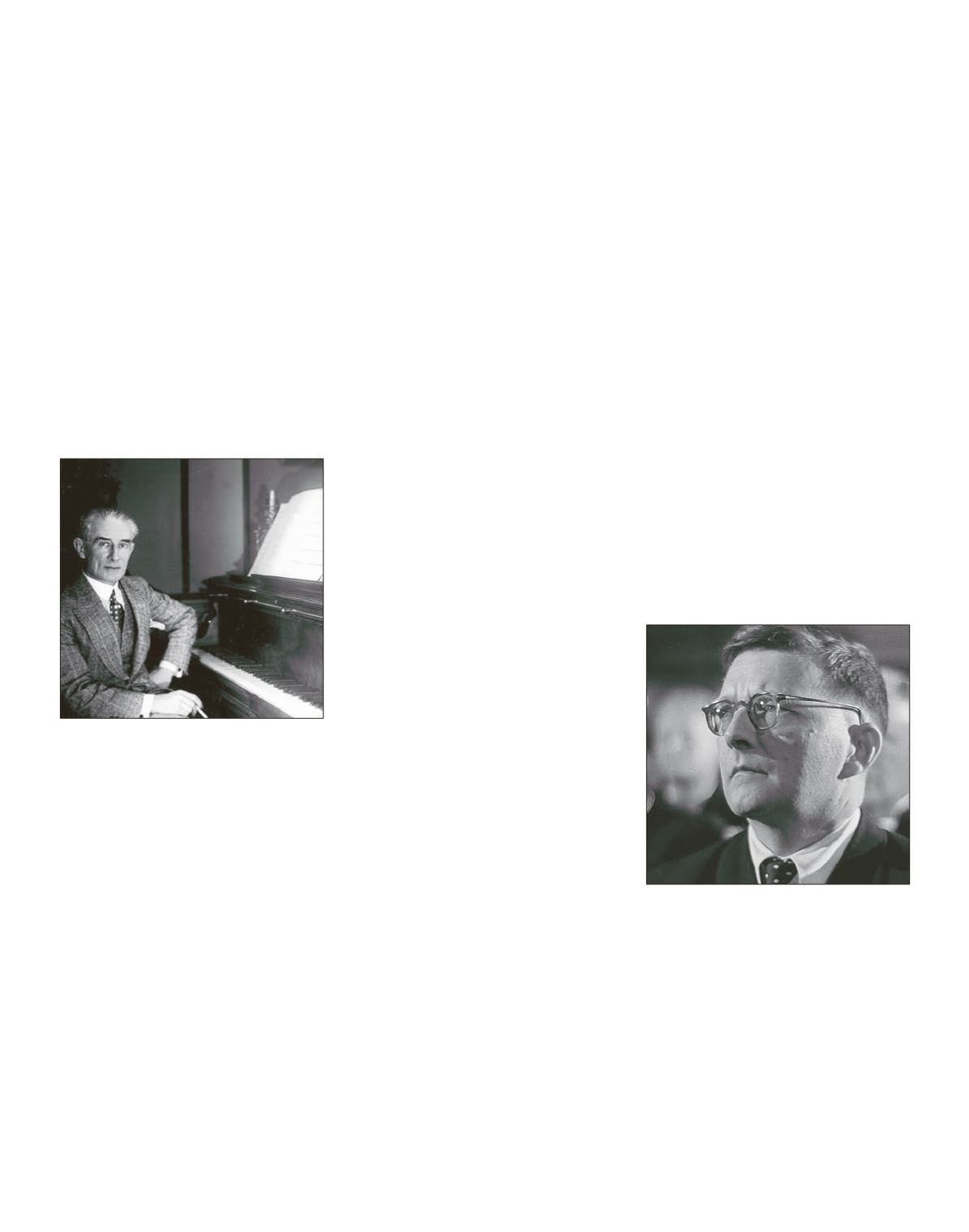

Maurice Ravel

Dmitri Shostakovich (1950)

RAVINIA MAGAZINE | AUGUST 13 – AUGUST 19, 2018

104