Rostropovich recognized that there might con-

sequence for his outspoken statements: “I know

that a er my letter there will undoubtedly be an

‘opinion

’ about me, but I am not afraid of it.” e

penalties were quick and extreme. Rostropovich

was banned from traveling abroad and from

giving performances in the USSR. Vishnevska-

ya, one of the principal sopranos at the Bolshoi,

was passed over for leading roles. In

, Ros-

tropovich requested and was granted permis-

sion to leave the Soviet Union: “Before that, I

was thinking of suicide. I thought everything

was lost.”

at approval followed the political

intervention of Senator Ted Kennedy, whom

Leonard Bernstein had encouraged to appeal

directly to General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev

during a trip to the Soviet Union. Following

a four-hour meeting between Kennedy and

Brezhnev in April

, the General Secretary

granted Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya their

two-year leave.

Initially, the couple traveled with their two chil-

dren to the United States, where they were feted

in private receptions (by Ted and Joan Kenne-

dy, among others) and public performances.

e time abroad, as the cellist later explained to

the

Washington Post

, was “not an escape from

Russia, but the only way to realize our musical

dreams by which we express our love for Russia

and our great people.”

In

, Rostropovich was named successor to

Antal Dorati as music director of the National

Symphony Orchestra; his -year tenure be-

gan in the fall of

. His immediate plans for

the National Symphony included a series of

world premieres, the orchestra’s rst recording

(Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto with soloist

Isaac Stern), its rst European tour at the end

of the

/ season, and a vision for a world-

class music conservatory in Washington, DC.

To open his rst season as music director, Ros-

tropovich invited pianist Rudolf Serkin to be

the soloist in Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.

across October – .

e following week (October – ) featured an

all-Bernstein concert—with no fewer than three

world premieres—on which the composer and

cellist shared time on the podium.

e major

new work

Songfest: A Cycle of American Poems

for Six Singers and Orchestra

occupied the sec-

ond half, conducted by Bernstein. Rostropovich

also ceded the baton to Bernstein to assume the

soloist role for the premiere of

ree Medita-

tions from Mass

, which Bernstein had arranged

for cello and orchestra expressly for the National

Symphony Orchestra and Rostropovich, at the

end of the rst half.

e concert opened with a “rousing new over-

ture” commissioned by Rostropovich entitled

Slava!

(A Political Overture), a deliberate dou-

ble-entendre on the Slavic word’s celebratory

meaning and the nickname of the composition’s

honoree. In this scintillating four-minute romp

in a “fast and amboyant” tempo, Bernstein

repurposed themes from his recent Broadway

op, the politically charged bicentennial musi-

cal

Pennsylvania Avenue

, which opened at

the Mark Hellinger eatre on May ,

, and

closed four days later.

Bernstein began his celebratory overture with a

variation on “ e Grand Old Party” from “ e

Money-Lovin’ Minstrel Parade” in Act Two of

Pennsylvania Avenue

.

ough not notated

in the score, it is traditional for the orchestra to

shout “Pooks” (the name of Rostropovich’s ubiq-

uitous long-haired miniature dachshund) with

the woodblock strike immediately before the

second theme. is

molto ritmico, con brio

(very

rhythmic, with re) melody in / —initially

scored for soprano saxophone and guitar; later

joined by horns in canon—is derived from the

upbeat “Rehearse!” heard in the opening scene

of

Pennsylvania Avenue

.

A short development section features a fugue

based on ve timeworn political proclamations,

pronounced above a vamping accompaniment.

Actors Michael Wager and Patrick O’Neal, lyr-

icist and playwright Adolph Green, and Bern-

stein taped these lines at a recording studio on

New York City’s East Side for playback during

the original performance.

“ … and if I am elected to this most high o ce,

I shall do everything in my power to bring about

the changes this country so desperately needs and

wants … ”

“ e people of this nation are sick and tired of the

abuses and misappropriations of power … ”

“Never again shall we submit to the dictatorial

evils of alien military power!”

“Permit me to quote the words of that mighty

statesman and champion of the downtrodden … ”

“I give you … the

!”

A erward, Bernstein reverses his original mate-

rial, starting with a fully orchestrated version of

the / theme. A brief piano interlude leads to a

recapitulation of the circus-march opening (mo-

mentarily broken by one phrase of the / theme)

and a robustly proclaimed “Slava!” at the end.

MAURICE RAVEL (1875–1937)

Piano Concerto in G major

Scored for ute and piccolo, oboe and English horn,

two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, trumpet,

trombone, timpani, triangle, snare drum, cymbals,

bass drum, tam-tam, wood block, whip, harp,

strings, and solo piano

e critical and monetary rewards of his rst

concert tour of the United States ( – ),

during which he conducted two performances

of his music with the Chicago Symphony Or-

chestra, encouraged Ravel to plan a return trip

for the early

s.

is time, he considered

appearances as solo pianist in an as-yet-unwrit-

ten concerto. Unexpectedly, the Austrian pia-

nist Paul Wittgenstein—who lost his right arm

during World War I—commissioned Ravel for

a le -hand concerto. He consequently found

himself in the remarkable position of writing

his rst two concertos simultaneously. His own

project was placed on hold while Ravel ful lled

the Wittgenstein commission over nine months

during

– . Ravel described this period to

London’s

Daily Telegraph

:

“Planning the two concertos simultaneously

was an interesting experience. e one in which

I shall appear as the interpreter is a concerto in

the truest sense of the word: I mean that I have

written very much in the spirit as those of Mo-

zart and Saint-Saëns.

e music of a concerto

should, in my opinion, be lighthearted and bril-

liant, and not aim at profundity or at dramatic

e ects. It has been said of certain great classics

that their concertos were written not ‘for,’ but

‘against’ the piano. I heartily agree. I had intend-

ed to entitle this concerto ‘Divertissement.’ en

it occurred to me that there was no need to do

so, because the very title ‘Concerto’ should be

su ciently clear.”

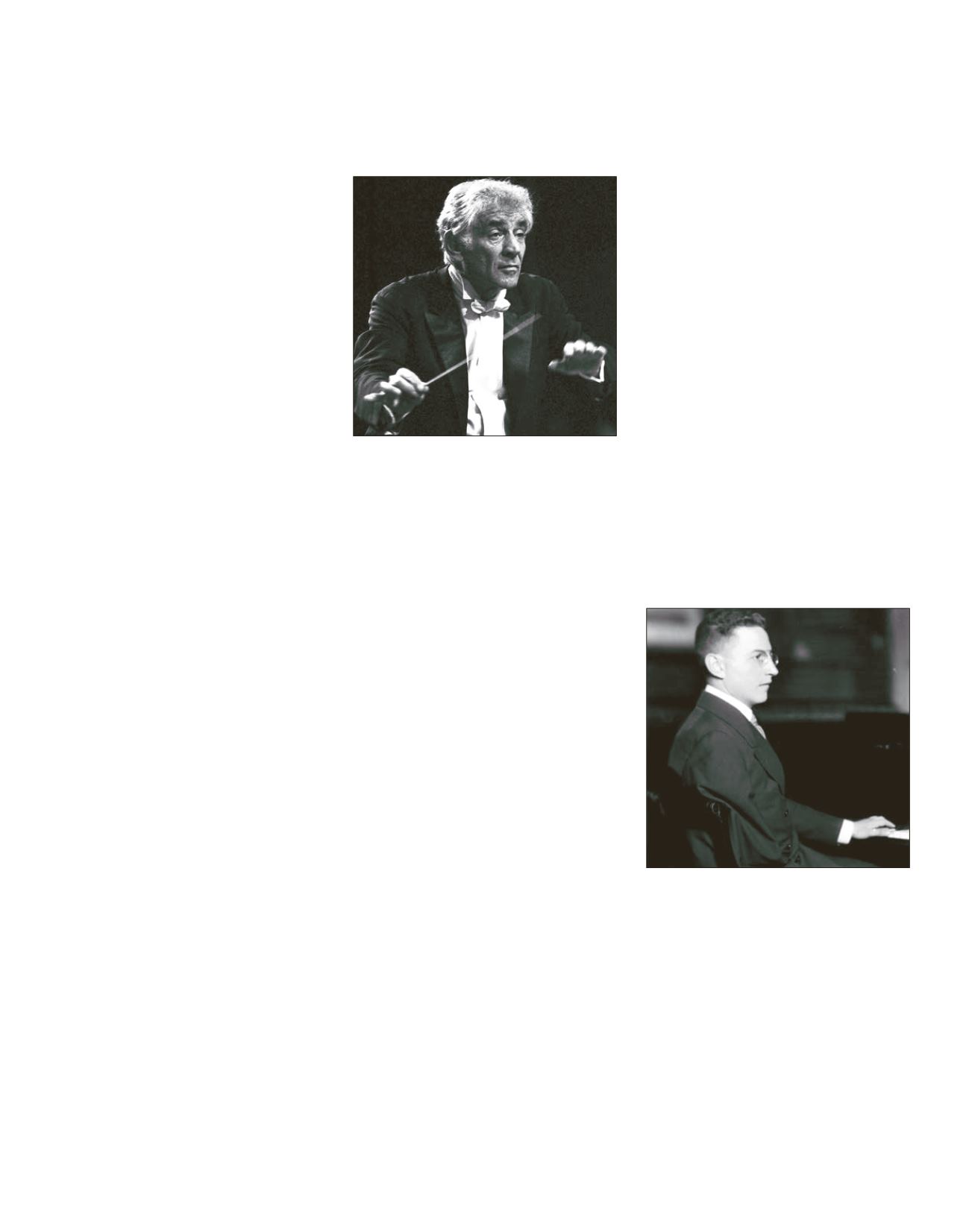

Leonard Bernstein (1976)

Paul Wittgenstein

AUGUST 13 – AUGUST 19, 2018 | RAVINIA MAGAZINE

103