LEONARD BERNSTEIN (1918–90)

Chichester Psalms

Scored for three trumpets, three trombones, timpani,

chime, suspended cymbals, cymbals, bass and

snare drums, xylophone, glockenspiel, tambourine,

triangle, woodblock, three bongos, whip, rasp, temple

block, two harps, strings, chorus, and boy solo

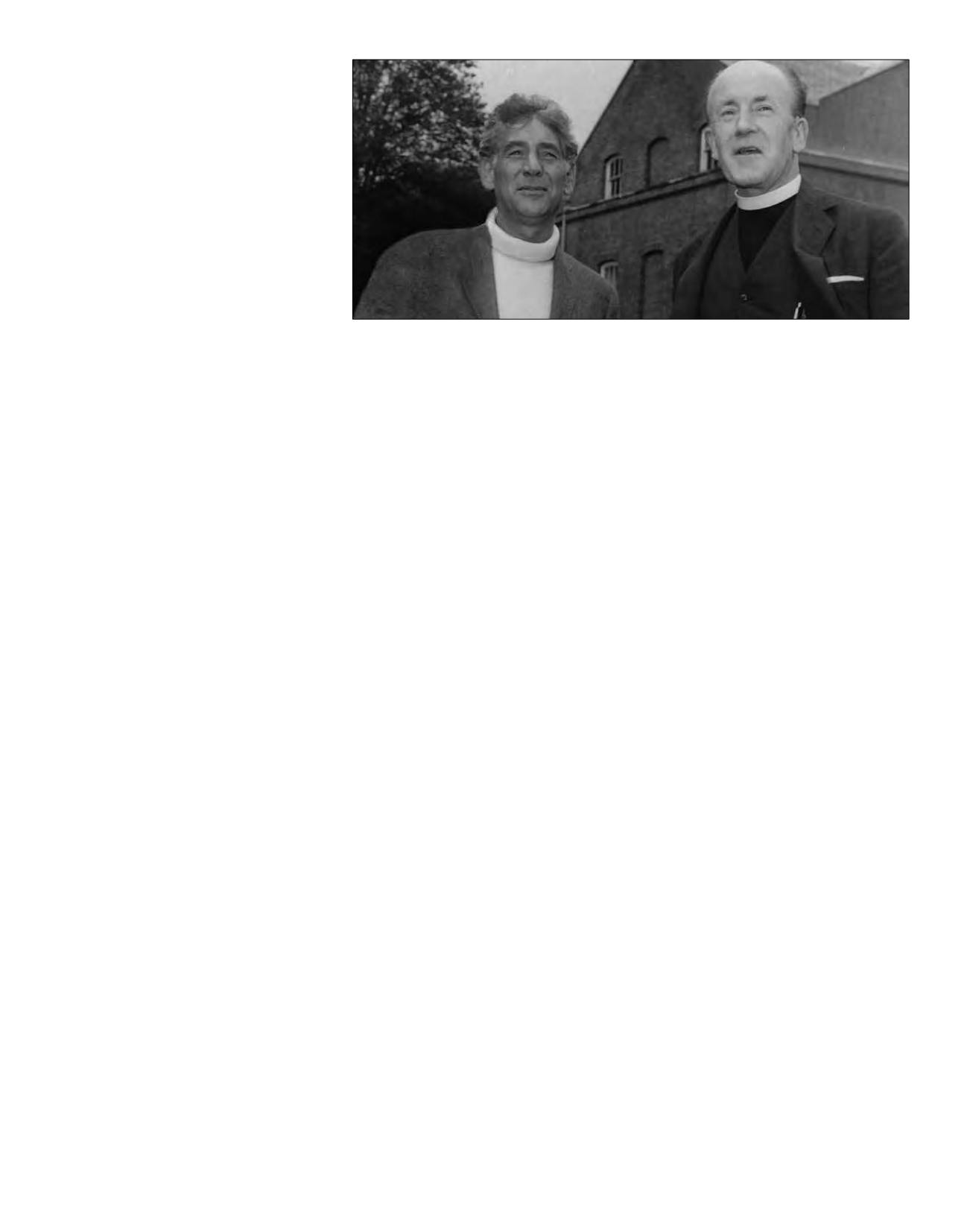

Leonard Bernstein’s personal physician, Cyril

(“Chuck”) Solomon, introduced his famous cli-

ent to the Very Reverend Walter Hussey (1909–

85), a visiting Anglican priest, after a rehearsal of

the New York Philharmonic in the early 1960s.

By then, Hussey had developed a widespread

reputation for commissioning contemporary

visual art and music, first as Vicar of Saint Mat-

thew’s Church in Northampton (1943–55) and

later as Dean of Chichester Cathedral (1955–77).

The encounter went no further than a brief

greeting until, a year or two later, Hussey mailed

Bernstein a letter via Dr. Solomon proposing a

new choral composition for the Southern Ca-

thedrals Festival.

The festival has taken place annually since its re-

vival in 1960 as a collaboration among the cathe-

dral choirs at Chichester, Winchester, and Salis-

bury, with each cathedral hosting the festival in

rotation. Hussey and organist-choirmaster John

Birch were determined to unveil a commis-

sioned work at the 1965 festival in its beautiful

Norman-Gothic sanctuary, as demonstration

that the English cathedral music tradition

“should not be regarded as a tradition which has

finished, and that we should be very much con-

cerned with music written today.” Bernstein’s

music, especially the musical-turned-film

West

Side Story

, which enjoyed widespread populari-

ty in England, captured the exciting potential of

modern music.

Hussey outlined his initial ideas in an introduc-

tory letter dated December 10, 1963: “The sort

of thing we had in mind was perhaps, say, a

setting of the Psalm 2, or some part of it, either

unaccompanied or accompanied by orchestra

or organ, or both.” Much to his surprise and

delight, Hussey received a reply on January 30,

1964, stating that Bernstein would be honored

to accept the commission, though he was uncer-

tain whether his schedule would allow work that

year or the following. Bernstein also requested

freedom to set other texts. Hussey responded

enthusiastically on February 10, granting lat-

itude in the literary selections. The Southern

Cathedrals Festival commission was under way.

A long period of silence followed, which Hus-

sey broke with a letter on August 14 outlining

the performing forces available at the festival:

combined choirs of 70–75 men and boys, strings

from the Philomusica of London, keyboards,

and a brass consort. The Chichester Dean wrote

again on December 22 with an exhortation to

write something that would provide English ca-

thedral music a “sharp and vigorous push into

the middle of the 20th century.” Bernstein re-

mained silent, understandably so since he had

begun a highly publicized 1964–65 sabbatical

from his post as music director of the New York

Philharmonic.

The music director duties left little time for Ber-

nstein to compose. Since accepting the position

in 1958, he had produced only one major com-

position: Symphony No. 3 (“Kaddish”), whose

premiere he conducted in Tel Aviv with the

Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, choruses, speak-

er Hannah Rovina, and mezzo-soprano Jennie

Tourel on December

10, 1963. His planned sab-

batical project marked a return to musical the-

ater, a form he had neglected since

West Side

Story

in 1957. In anticipation of his leave, Ber-

nstein began assembling an artistic team for a

musical setting of Thornton Wilder’s Pulitzer

Prize–winning 1942 play

The Skin of Our Teeth

.

Wilder granted adaptation rights to lyricists Bet-

ty Comden and Adolph Green. Bernstein’s date-

book records meetings—often dinners—with

Comden and/or Green beginning in May 1964.

Director and choreographer Jerome Robbins

came onboard sometime in early September.

The

New York Times

announced the

Skin of Our

Teeth

project on September

4, 1964. Columbia

Broadcasting System would serve as sole un-

derwriter, and the opening was announced for

September 1965. The four collaborators contin-

ued to meet periodically during the fall. Lela

Hayward agreed to produce the musical. Bern-

stein, his wife Felicia, and their children Jamie,

Alexander, and Nina, departed for Chile, where

they would spend the holidays with Felicia’s

family. On January

5, 1965, The

New York Times

announced the termination of the project. Ber-

nstein conveyed his profound disappointment

in a poetic sabbatical report published months

later by the newspaper, on October

24, 1965:

“We gave it up, and went our several ways,

/ Still

loving friends; but there was the pain

/ Of seeing

six months of work go down the drain.”

Now lacking a sabbatical project, Bernstein refo-

cused attention on the Southern Cathedrals Fes-

tival commission and resumed correspondence

with Dean Hussey. He outlined an expanded

conception for the choral work on February 24,

1965: “a suite of Psalms, or selected verses from

Psalms [Psalms 2, 23, 100, 108, and 131], and it

would have a general title like

Psalms of Youth

.

The music is all very forthright, songful, rhyth-

mic, youthful. The only hitch is this: I can think

of these Psalms only in the original Hebrew.”

Hussey assured Bernstein there would be no li-

turgical objection to Hebrew texts, though they

could challenge the singers and audience and

thus should be printed phonetically.

Though he composed primarily in his Manhat-

tan apartment, Bernstein completed the draft

score on May 7 at his home in Fairfield, CT.

Four days later, he wrote triumphantly to Hus-

sey: “The Psalms are finished, Laus Deo, are be-

ing copied, and should arrive in England next

week.” Bernstein anticipated completion of the

orchestration in June with delivery of the full

score and parts in time for rehearsals in Chich-

ester. He professed satisfaction with the score

and proudly announced to Hussey, “It is quite

popular in feeling (even a hint, as you suggested,

of

West Side Story

).”

Under its new title,

Chichester Psalms

, the

composition is divided into three movements,

which Bernstein outlined in literary, musical,

and spiritual terms. The first movement opens

with a chorale-like setting of the praise-filled

third verse from Psalm 108 and the entire Psalm

100, with its joyous dance. The next movement

begins with an innocent setting of Psalm 23 for

boy soprano and harp that is “interrupted sav-

agely by the men with threats of war and vio-

lence,” based on Psalm 2. The final movement of

the “suite” opens with an acerbic variation of the

opening chorale for orchestra that surrenders to

the simplistic, peaceful Psalm 131, “something

like a love duet between the men and the boys,”

in the composer’s words.

In the same letter, Bernstein mentioned chang-

es in instrumentation (the addition of percus-

sion and increasing the number of strings) then

dropped a bombshell. The New York Philhar-

monic had invited him to conduct a concert

Leonard Bernstein with the Very Reverend Walter Hussey, Dean of Chichester Cathedral

RAVINIA MAGAZINE | JULY 9 – JULY 15, 2018

110