satisfaction of the participants. Dean Hussey

was elated: “We were all thrilled with them. I

was specially excited that they came into being

at all as a statement of praise that is ecumenical.”

The British press was somewhat uncharacter-

istically gracious in its reviews. As an example,

The Times

of London praised the mixture of

concert and popular styles in the “three excit-

ing, imaginative movements.” Unbenownst to

the performers or audience, there was a secret

explanation for the popular element: five themes

were composed for musical theater works, four

from

The Skin of Our Teeth

and one that had

been cut from

West Side Story

. The first move-

ment incorporates the “Chorale: Save the World

Today” (Psalm 108) and “Here Comes the Sun”

(Psalm 100), both from

The Skin of Our Teeth

.

Two more rescued themes appeared in the sec-

ond movement: “Spring Will Come Again” from

The Skin of Our Teeth

(Psalm 23) and the

West

Side Story

cut “Mix” (Psalm 2). The setting of

Psalm 131 in the final movement recirculates the

“War Duet” from

The Skin of Our Teeth

.

Over the course of 19 months, Bernstein had de-

veloped a warm friendship with and admiration

for Walter Hussey. The composer sent an auto-

graphed copy of the full score to his Anglican

colleague for inclusion in the Chichester Cathe-

dral archives and dedicated the published score

to both Hussey and Chuck Solomon, who was

responsible for initiating the project. The rela-

tionship between commissioner and composer,

as recorded in their letters, has since formed

the basis of the play

Walter & Lenny

, devised

and performed by Peter McEnery for the 50th

anniversary of the

Chichester Psalms

. This one-

man show opened on November 11, 2015, at the

Minerva Theatre in Chichester, followed by a

production at the 50th Bedford Park Festival in

London in June 2016. This year, the Chichester

Cathedral will present

Walter & Lenny

on Sep-

tember 5–8 in honor of the centennial of Bern-

stein’s birth.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770–1827)

Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op. 125

Scored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two

bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, timpani, strings,

chorus, and solo vocal quartet

Few works of art elevate, inspire, and mystify

with the same indescribable power that Beetho-

ven’s Symphony No. 9 possesses. The music dra-

mas of Richard Wagner and the symphonies of

Gustav Mahler, to name a few, owe their very ex-

istence to this work. Gustav Klimt’s wonderfully

sensual, art nouveau

Beethoven Frieze

embodies

a personal reflection on the Ninth Symphony.

Musical analyses of this complex score (such as

Heinrich Schenker’s tome) have filled volumes.

The depth of meaning in Beethoven’s inspired

setting of Friedrich von Schiller’s “Ode to Joy”

has not been exhausted. It probably never will be.

Even before moving to Vienna permanent-

ly in 1793, Beethoven announced his desire to

compose music for the “Ode to Joy.” The idea

of including this text in a symphony, though,

struck with jarring force 30 years later. Anton

Schindler, Beethoven’s secretary and biogra-

pher, remembered the magical moment: “One

day, when I entered his room, he called out to

me, ‘I have it! I have it,’ holding out his sketch-

book, where I read these words, ‘Let us sing the

immortal Schiller’s song,

Freude

.’ ” At that mo-

ment, the master solved the aesthetic impasse

presented by the final movement. Borrowing a

notion (and actual melodic phrases) from his

Choral Fantasy, op. 80, for piano, orchestra, and

chorus, Beethoven made the unprecedented de-

cision to incorporate chorus and vocal soloists

into his symphony. However, Schiller’s drinking

song text required patient selection and rewrit-

ing to extol universal peace and brotherhood.

Although the Symphony No. 9 originated as a

work for the Philharmonic Society of London,

its premiere took place May 7, 1824, in Vienna

on a monumental program with the Overture

to

Consecration of the House

, op. 124, and three

movements from the

Missa solemnis

, op. 123. To-

tally deaf, the composer stood beside conductor

Ignaz Umlauf, beating time and turning pages.

Beethoven negotiated with several publishers

for rights to the Symphony No. 9, which he fi-

nally offered to the Mainz firm B. Schott and

Sons. The printed score, complete with metro-

nome markings and lavish title page, was dedi-

cated to Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia.

Structurally, the Symphony No. 9 remains within

accepted boundaries of early Romantic instru-

mental practice: sonata-form first movement,

scherzo–trio–scherzo, slow variations, and fast

sonata-rondo. However, Beethoven saturates his

movements with a bounteous stream of melod-

ic motives, rhythmic energy, daring harmonic

progressions, and developmental expansion

that stretch standard forms to the point of de-

struction and irrelevance. His colossal expres-

sion dominates every aspect of the music and

in the final movement demands both a larger

of his own music in early July, and he planned

to include the first performance of

Chichester

Psalms

. “I realize this would deprive you of the

world premiere by a couple of weeks,” he wrote

to Hussey, “do you have any serious objections?”

Bernstein received a reply on May 19, not from

the dean, who was recovering from illness, but

from the precentor, D.R. Hitchinson, who wrote

candidly, “I do feel strongly, however, that the

dean would be most unhappy and disappoint-

ed if the

Chichester Psalms

were not to have the

world premiere in Chichester.”

The pace of correspondence accelerated as the

Southern Cathedrals Festival approached. On

June 11, Hussey invited Bernstein to conduct

the festival performance. Eighteen days later,

Hussey gave his approval to the New York Phil-

harmonic performance and proposed that the

entire Bernstein family make the trip, offering

to house them at the deanery since all the local

hotels were booked for race week at the Good-

wood Racecourse. In the end, Lenny and Felicia

stayed in the deanery, and Jamie and Alexander

(Nina remained behind in the US) boarded with

a local family who had children their ages.

Meanwhile, Bernstein conducted the premiere

of

Chichester Psalms

on July 15 and 16 with the

New York Philharmonic and Camerata Singers,

an interpretation immediately recorded for Co-

lumbia Records. The Bernstein family departed

New York City for London on July 27, arriving in

Chichester the following day. A couple days of

family sightseeing followed, and then the only

rehearsal on the day of the July 31 performance,

which Bernstein assured Hussey was the “real

premiere” because it involved a choir of men

and boys, as originally intended. The composer

later summarized the performance for his per-

sonal assistant, Helen Coates: “The

Psalms

went

off well, in spite of a shockingly small amount

of rehearsal. The choirs were a delight! They

had everything down pat, but the orchestra was

swimming in an open sea. They simply didn’t

know it.”

None of this dampened the enthusiasm and

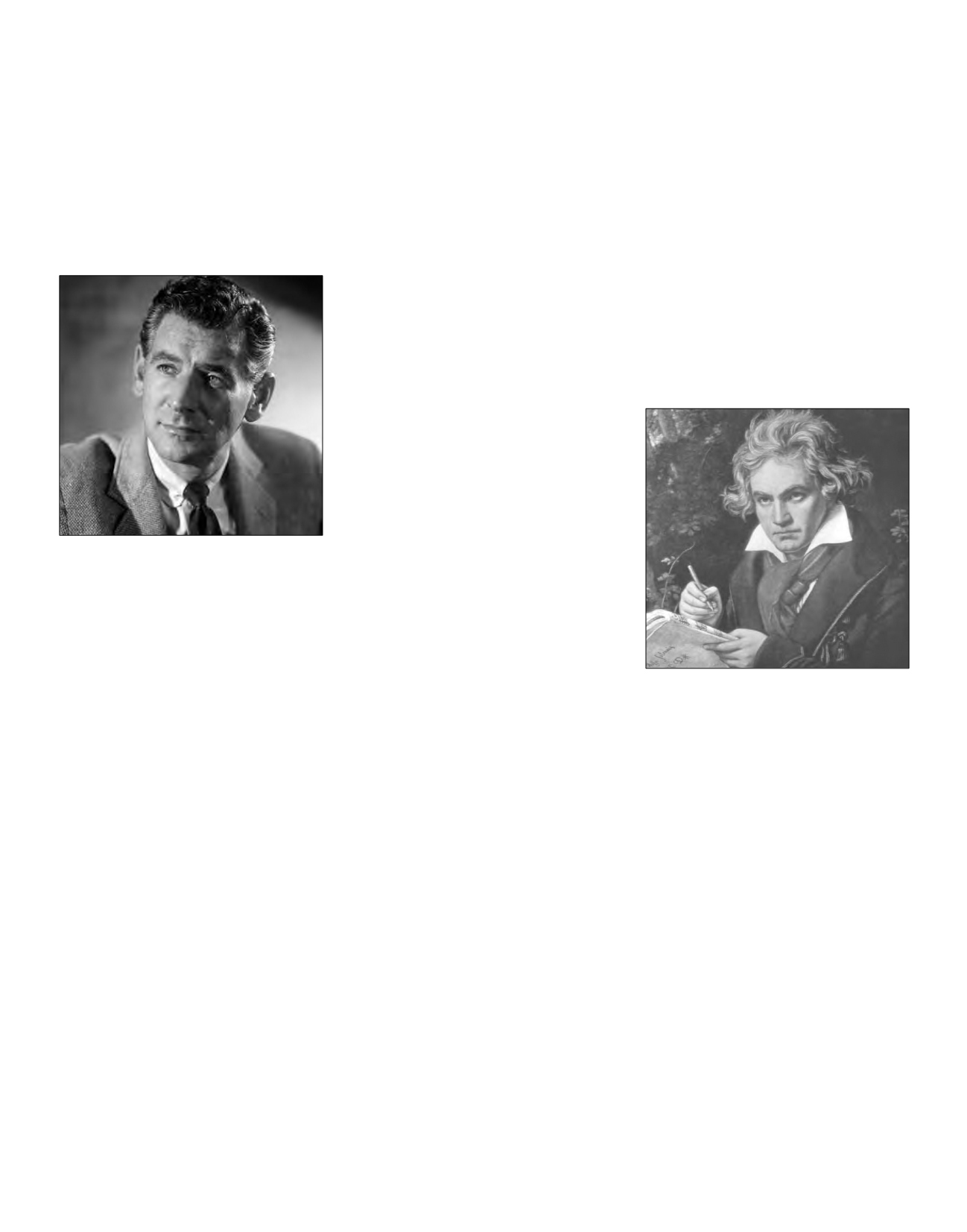

Ludwig van Beethoven by Joseph Karl Stieler (1820)

Leonard Bernstein

JULY 9 – JULY 15, 2018 | RAVINIA MAGAZINE

111