“Meanwhile I am composing six easy clavier so-

natas for Princess Friederike and six quartets for

the king, all of which Kozeluch is engraving at

my expense.” However, Mozart completed only

one sonata and three quartets. Almost one year

later, he con ded in Puchberg, “I have now been

forced to give away my quartets (that exhausting

labor) for a mere song, simply in order to have

cash in hand to meet my present di culties.”

ese works did not appear until a er Mozart’s

death, without a dedication to the Prussian king.

Was the “commission” a reality or a ruse? Surely

the cash-strapped composer would have bene-

ted from genuine royal patronage. Some spec-

ulate that Mozart invented the “commission” to

appease Puchberg (he was heavily in debt to his

Masonic brother) or to cover up a rumored af-

fair with an opera singer, perhaps Josepha Dus-

chek, who turned up “unexpectedly” at every

city on his journey.

Musical elements argue in support of an in-

tended royal patron. King Friedrich Wilhelm II

regularly participated as a cellist in performanc-

es of chamber music with his court musicians.

e rst “Prussian” Quartet in D major, .

,

spotlights the royal instrument in numerous

high-lying lines. Mozart also explored an un-

familiar popular idiom—simple

cantabile

mel-

odies and moderate tempos (three movements

are

Allegretto

and the “slow” movement is a me-

dium-paced

Andante

)—which may have posed

his greatest compositional challenge.

Instrumental dialogue, as exempli ed by the

rst-violin and viola exchange in the opening

Allegretto

theme, also forms part of the popu-

lar style. A second instrumental pairing, of cello

and second violin, continues this simple melod-

ic exchange in the secondary theme. e

Andan-

te

begins with a hushed ensemble idea, and then

the rst violin and cello engage in alternating

melodic phrases. Typical dance-like vigor char-

acterizes the

Menuetto

; Mozart spotlights the

cello in a contrasting

trio

.

e sparkling rondo

nale combines a cello refrain theme (derived

from the rst-movement melody) with a viola

counterpoint. Unable to sacri ce his sense of

cra completely to popular demands, Mozart

also manipulated this melody through inversion

and other contrapuntal devices.

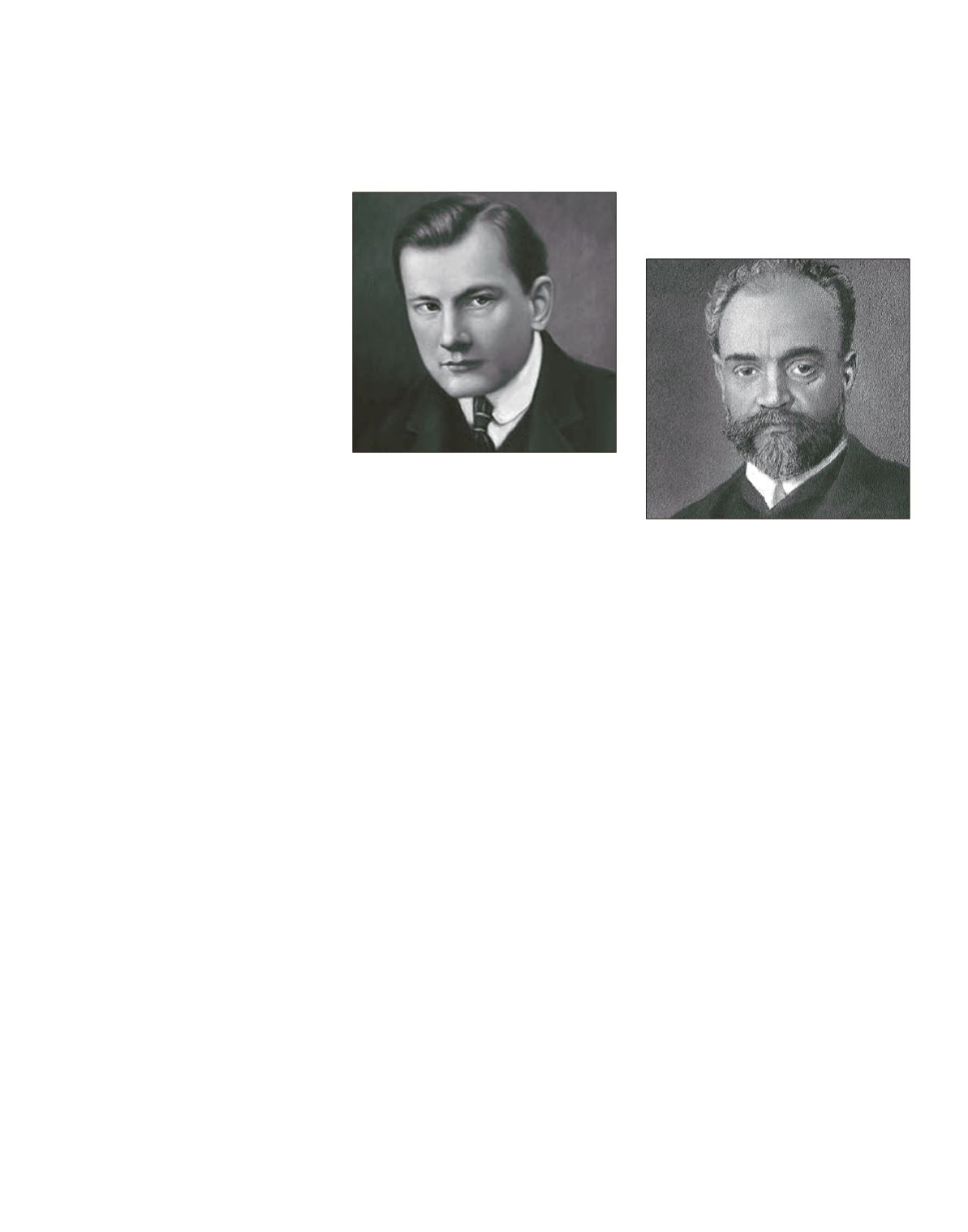

ERNĆ DOHNN<I (1877–1960)

String Quartet No. in D- at major, op.

Ernő Dohnányi almost single-handedly upheld

musical standards in his native Hungary be-

tween the monumental careers of Franz Liszt

and Béla Bartók. His father, Friedrich, a pro-

fessor of mathematics and physics in Pozsony

(Bratislava) and an amateur cellist, oversaw

Ernő’s introduction to the piano. A promising

future was predicted for young Dohnányi, who

matriculated at the Royal Academy of Music in

Budapest in

.

Composition proved as attractive to Dohnányi

as the piano. e Piano Quintet No. in C mi-

nor, op. , elicited praise from the typically re-

served Johannes Brahms, who immediately ar-

ranged for performances in Ischl and Vienna.

Dohnányi met with Brahms several times before

the elder composer’s death in

.

Following his graduation, Dohnányi embarked

on toured throughout Europe, England, and

the United States. He joined the faculty at the

Hochschule für Musik in Berlin in

and

was named a professor in

. Seven years lat-

er, Dohnányi returned to Budapest to serve as

director of the Philharmonic Orchestra Society

and the Royal Academy of Music. e changing

political climate in Hungary forced Dohnányi to

leave his country. He settled in the United States

in

, serving on the music faculty at Florida

State University for a decade and becoming an

American citizen in

.

Hallmarks of Dohnányi’s style abound in the

String Quartet No. in D- at major, op.

(

): rich harmonies lightly tinged with chro-

maticism, compact themes with motives ripe

for development, and cyclic uni cation. Small

gestures embedded in the opening phrase pro-

vide material for the whole rst movement: a

pair of slow, rising pitches, a downward leap,

an ascending arpeggio, and a dotted rhythm.

Tempos change frequently.

e

Presto acciaca-

to

(“acciacato” means “crushed” or “squashed”)

is a

toccata

movement with a folk-like thematic

simplicity. A gentle melody provides contrast in

the middle of the movement. Quiet, expressive

writing introduces the nal movement. Animat-

ed sections spoil the tranquility. Toward the end,

themes from the rst two movements are heard

one last time.

ANTONN D9OĎ. (1841–1904)

String Quartet No. in E- at major, .

e astonishing nancial success of his rst pub-

lished scores made it very di cult for Dvořák to

avoid being typecast as a folk-inspired composer.

Johannes Brahms had recommended the young

Czech musician to his own publisher, Fritz Sim-

rock, who amassed a near fortune from sales of

the Moravian Duets (composed

; published

), the rst set of Slavonic Dances ( ), and

the Slavonic Rhapsodies ( ). Quite naturally,

the business-minded publisher longed for other

pro table ethnic works. Dvořák, on the other

hand, sought a wider representation of his art

before the public and promoted music in more

traditional genres to Simrock.

In the short run, Dvořák persuaded his publish-

er to issue only a small number of these standard

works. e select list included his String Sextet

in A major, .

( ), a work that received its

premiere in Berlin on November ,

, mak-

ing it the rst piece to be rst heard outside the

composer’s homeland. Before that public event,

the Joachim Quartet gave a private reading on

July ,

. is intimate recital in Joseph Joa-

chim’s residence also included another recent

chamber piece issued by Simrock—the String

Quartet No. in E- at major, .

.

A more complete musician emerged from every

page of the quartet, one possessing a sophisticat-

ed technique, mastery of form, and multi-dimen-

sioned expression.

e

Allegro ma non troppo

remains largely in a mode of restrained passion,

especially in its hymn-like episode during the

development.

is lyrical, emotionally concen-

trated vein returns in the

Romanze

. Further-

more, Dvořák attained a comfortable coexis-

tence of “Classical” and ethnic ingredients.

e

quartet includes an elegiac second movement in

Dumka

style, a soulful Czech folk piece in slow

tempo. Here, cello pizzicatos provide an evoca-

tive accompaniment to a minor-key “duet.” In

time-honored fashion, Dvořák contrasts this

mournful material with a lively

furiant

dance that

shi s rapidly between two- and three-beat rhyth-

mic patterns.

e

Finale

’s main theme likewise

pays homage to folk dance traditions, perhaps (as

Dvořák scholar Alec Robertson has suggested)

the reel-like

skočna

.

–Program notes ©

Todd E. Sullivan

(UQć 'RKQ£Q\L

AQWRQ¯Q 'YRď£N

JULY 30 – AUGUST 5, 2018 | RAVINIA MAGAZINE

99