In writing his

Don Giovanni

libretto, Da Ponte

built upon the centuries-old theatrical tradition

surrounding Don Juan. He also drew character

material from his conversations with the notori-

ous, real-life Giacomo Casanova, whom he had

known in Venice and who now lived outside

Prague. Mozart arrived in Prague on October

,

— days before the scheduled premiere—

with an incomplete score in hand. Da Ponte

reached the Bohemian capital three days later

to oversee the staging. e National eater was

not ready in time for the announced opening

date, and performances were postponed twice.

Don Giovanni

eventually reached the stage on

October .

In Act One, the audience encounters the libid-

inous Don Giovanni, who bounds from one

amorous conquest to the next. Donna Elvira en-

ters, bemoaning her abandonment by a rogue.

Don Giovanni consoles Donna Elvira—neither

recognizing the other at rst—as Leporello

comments sarcastically on his master’s special

type of comfort. When the Don kisses Donna

Elvira’s hand, she realizes he is the o ender. Don

Giovanni ees, leaving Leporello to outline a

long history of seductions (“Madamina, il cat-

alogo è questa”). Having done nothing to cheer

up Donna Elvira, Leporello departs.

Leporello and Don Giovanni stagger into a

wooded square outside Donna Elvira’s abode

at the beginning of Act Two. Leporello again

expresses his desire to leave Giovanni’s service,

an issue soon silenced by a bag of coins and a

failed attempt to reform his master’s lecherous

ways (“Eh via bu one”). Incensed, Don Giovan-

ni spouts that remaining faithful to one woman

would make so many others unhappy. He con-

vinces Leporello to exchange cloaks and stand in

the open square while Don Giovanni sings a ser-

enade to Donna Elvira. e music soothes, and

Donna Elvira descends from her room when the

suitor threatens suicide. Making like a robber,

Giovanni frightens the cloaked Leporello and

Donna Elvira away. Giovanni picks up the man-

dolin and serenades Elvira’s maid (“Deh, vieni

alla nestra, o mio tesoro”).

RUGGERO LEONCAVALLO (1857–1919)

Intermezzo from

Pagliacci

e Neapolitan composer and librettist Ruggero

Leoncavallo enjoyed a privileged upbringing as

the son of a wealthy judge. A er studies at the

Conservatorio di Musica San Pietro a Majella,

which the composer Paolo Tosti had attended

a decade earlier, Leoncavallo embarked on a

performing and teaching career while compos-

ing Italian operas and songs on the side. Cap-

italizing on the political in uence of his uncle

Giuseppe, who served in the Foreign Ministry,

Leoncavallo became pianist and piano teacher

to the brother of the Khedive Twe k Pasha in

Egypt, remaining until the uprising of

.

Initially, Leoncavallo ed to Paris to circulate

among late-Romantic artists, writers, and mu-

sicians. He returned to Italy early in the next

decade, taking up residence in Milan.

e tri-

umphant

premiere of Pietro Mascagni’s

verismo opera

Cavalleria rusticana

in Rome

changed the course of Leoncavallo’s composi-

tional style. Within two years, he produced his

own masterpiece of verismo opera,

Pagliacci

(

Clowns

), which premiered at Milan’s Teatro Dal

Verme on May ,

.

Leoncavallo wrote his own libretto, basing the

story on a haunting childhood episode.

e

brothers Luigi and Giovanni D’Alessandro killed

a family friend and young Ruggero’s sometime

babysitter, the -year-old Gaetano Scavello, in

. Jealousy over Gaetano’s alleged romance

with a woman who also was involved with Lu-

igi D’Alessandro prompted the murder by knife.

e judge who convicted the brothers was Leon-

cavallo’s father, Vincenzo. In

Pagliacci

, Leonca-

vallo sensationalized this case through an op-

eratic love triangle involving Canio, the leader

of a traveling troupe of actors/clowns, his wife

Nedda, and her alleged lover, the hunchback ac-

tor Tonio.

JULES MASSENET (1842–1912)

“Vision fugitive” from

Hérodiade

Massenet triumphed in the world of grand op-

era with his four-act realization of the biblical

story of John the Baptist, the young maiden Sa-

lome, the tetrarch Herod, and his wife Herodi-

as—

Hérodiade

( ). e opera’s literary source

was Gustave Flaubert’s “Hérodias, le conte de

Salomé” found in the collection

Trois Contes

( ree Tales;

). Like in Oscar Wilde’s infa-

mous play

Salome

nearly two decades later (it-

self heavily indebted to Flaubert; also the basis

of Richard Strauss’s opera of the same name),

Flaubert weaves an intriguing tale of lust and

power, loyalty and betrayal.

Hérodiade

opened

on December

,

, at the éâtre de la Mon-

naie in Brussels.

Like Flaubert’s story, the libretto by Paul Milliet

and Henri Grémont (pseudonym for Georges

Hartmann) treats the biblical tale rather loosely.

Salome—orphaned and unaware of her parent-

age—has become an ardent disciple of John the

Baptist, who rescued her as a child (“Il est doux,

il est bon”). Herod becomes obsessed with the

beautiful Salome.

ough a troupe of graceful

women dance in his chamber, he prefers the

potion-induced apparition of Salome (“Vision

fugitive”). Consulting the Chaldean astrologer

Phanuel, Herodias discovers that Salome is the

child she abandoned in order to marry Herod.

Salome remains faithful to John, despite Herod’s

lecherous advances. e Baptist receives a death

sentence, and Salome stands ready to die with

him. She dances before Herod, begging mercy

for John. However, the executioner arrives with

a sword stained in John the Baptist’s blood. A

distraught Salome grabs a dagger and attacks

Herodias, who exclaims, “I am your mother!”

Salome turns the blade on herself.

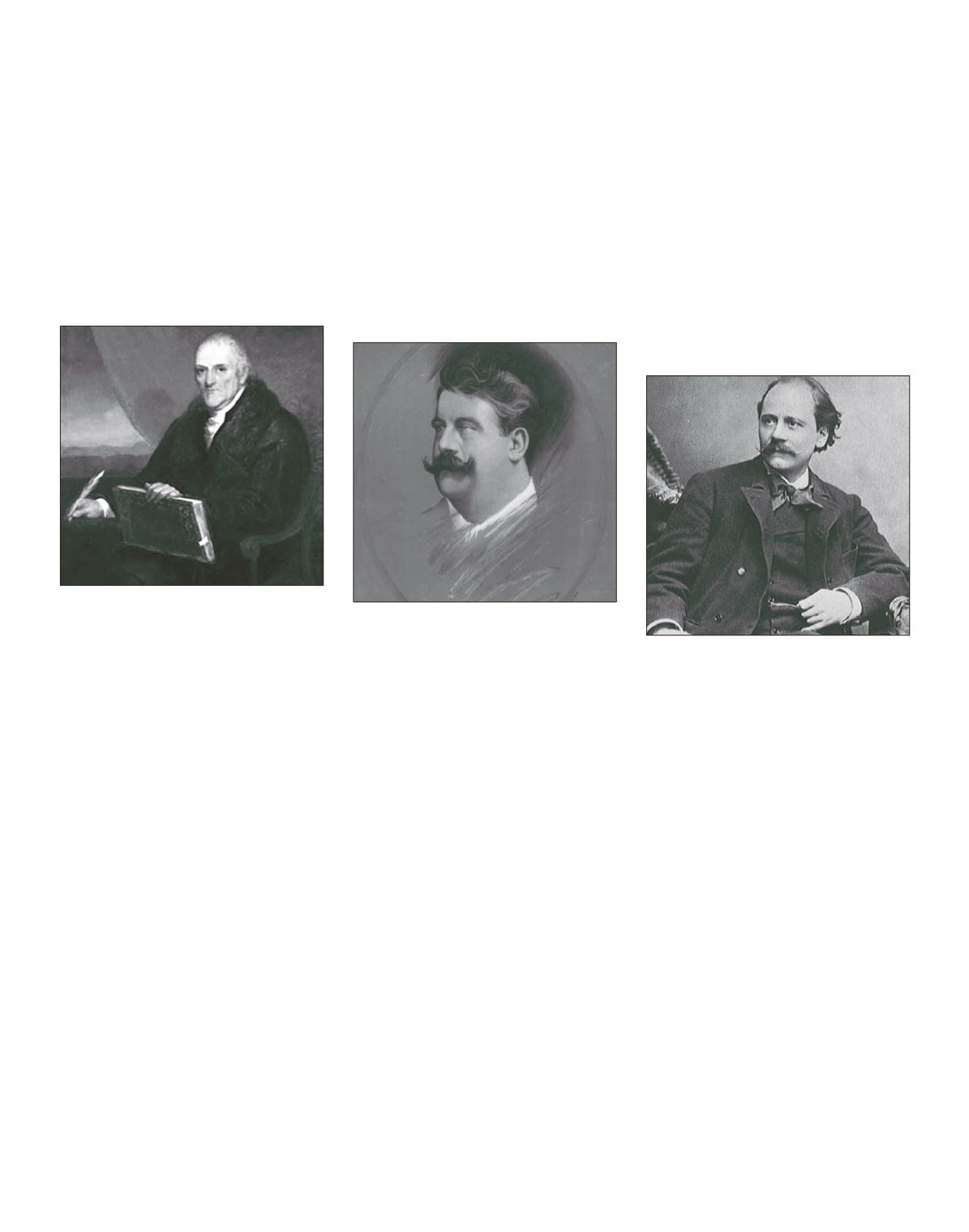

Ruggero Leoncavallo

Lorenzo Da Ponte

Jules Massenet

AUGUST 6 – AUGUST 12, 2018 | RAVINIA MAGAZINE

101