Broadway collaboration of composer George

Gershwin and his lyricist brother Ira.

Funny

Face

became the rst show produced at the new-

ly constructed Alvin

eatre, where it opened

on November ,

. Fred and Adele Astaire

again appeared as siblings, Jimmy Reeve and his

younger sister Frankie.

e music of

MARVIN HAMLISCH (1944–

2012)

made his name a household word—from

the theme song and score to the motion picture

e Way We Were

to his adaptation of Scott Jo-

plin’s music in

e Sting

to his smash-hit musi-

cal

A Chorus Line

. Kevin Cole’s

Marvin’s Medley

surveys award-winning songs from the

s:

the title theme from

e Way We Were

and “At

the Ballet” and “What I Did for Love” from

A

Chorus Line

.

e Way We Were

( ) earned

Hamlisch two Academy Awards, for Best Origi-

nal Dramatic Score, and Best Original Song (for

“ e Way We Were”). Later in the decade came

A Chorus Line

(

), which earned Hamlisch a

Tony Award, the New York Drama Critics’ Cir-

cle Award, the

eatre World Award, and the

Pulitzer Prize, and was then the longest-running

Broadway show in history.

e team of

RICHARD RODGERS

and Oscar

Hammerstein II completed a new musical about

once every two years.

Carousel

, based on the play

Liliom

by Ferenc Molnár, was nished in

.

e original run at the Majestic eatre, open-

ing on April , lasted for

performances.

e co-creators decided to reduce the amount

of spoken dialogue in order to focus more atten-

tion on the musical numbers. Molnár’s Budapest

carnival barker Liliom underwent few transfor-

mations to become Billy Bigelow, the New En-

gland carnival barker. Billy, a shi y and boastful

character, falls in love with the virtuous Julie.

ey marry and have a daughter. When Billy

loses his job, he turns to crime and is shot dead

during a robbery attempt. Years later, he is of-

fered one chance to redeem himself. He attends

his daughter’s graduation as a spectral observer,

and restores her broken con dence.

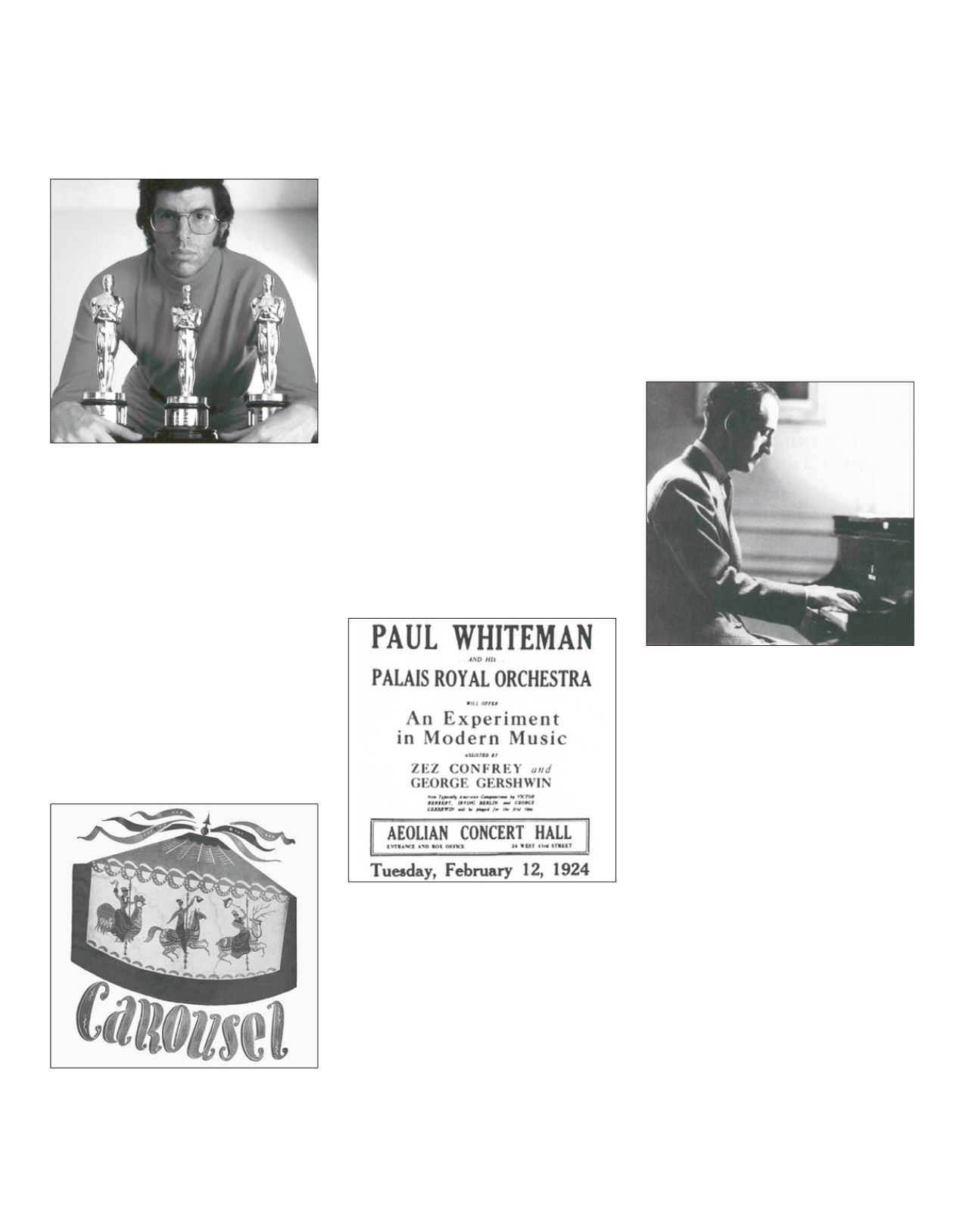

Paul Whiteman announced a provocative con-

cert in the

New York Tribune

on January ,

.

e stated purpose of this musical event was to

decide “What is American music?” According

to the four-paragraph article, Whiteman had

assembled a distinguished panel of musicians

to decide the question. Among other music, the

program would contain three new composi-

tions: a jazz concerto by

GEORGE GERSHWIN

,

a “syncopated tone poem” by Irving Berlin, and

an American suite by Victor Herbert. Ira Ger-

shwin brought this article to his brother’s atten-

tion. George apparently had forgotten about the

“jazz concerto” project, which he had discussed

only in vague terms with Whiteman. With less

than six weeks before the concert, the surprised

musician began mapping out ideas.

Gershwin’s account of the creative process

appeared in

, one year a er his tragic death

from brain cancer: “I had no set plan, no struc-

ture to which my music must conform.

e

Rhapsody

, you see, began as a purpose, not as

a plan.” Shuttling between New York and Bos-

ton for the tryout of his musical

e Perfect

Lady

(produced on Broadway as

Sweet Little

Devil

), Gershwin’s imagination came alive to

the sounds of his passenger train “with its steely

rhythms, its rattlety-bang … I suddenly heard—

even saw on paper—the complete construction

of the

Rhapsody

from beginning to end.” Ger-

shwin imagined a grand nationalistic essay, “a

musical kaleidoscope of America—of our vast

melting pot, of our incomparable national pep,

our blues, our metropolitan madness.”

Whiteman’s “An Experiment in Modern

Music” took place as scheduled on February .

Countless socialites and musical dignitaries

crowded Aeolian Hall for this major event.

Rhapsody in Blue

occupied the next-to-last sec-

tion. Given the press of time, Gershwin allowed

Ferde Grofé to orchestrate the score. Whiteman

conducted from an incomplete score. Gershwin

improvised many solo piano passages, then nod-

ded to the conductor when the orchestra should

enter. Rhapsodic elements exist in the numerous

tempo changes and the long unaccompanied pi-

ano solos. e speci c tempo sequence might be

viewed as a compressed symphony: moderate-

ly fast, scherzo, slow “love” theme, and toccata

nale.

Sheer melodic abundance disguises the care-

ful unity of Gershwin’s themes. All utilize the

blues scale (major and minor thirds and minor

seventh) and two share a common syncopat-

ed rhythm.

e exact sequence and selection

of themes varies considerably in di erent per-

forming versions, raising the perplexing ques-

tion: What exactly constitutes the

Rhapsody in

Blue?

is nebulous situation existed from the

very origins of the work and has persisted to the

present day. Gershwin le three recordings, two

with Whiteman’s ensemble and one piano roll

recorded in two sessions.

e “orchestral” ver-

sions have been signi cantly abridged, while the

piano version gives a more complete rendition.

Oddly, the clearest yet most sterile de nition of

this piece exists in copyright law: six melodies

and a motivic tag, any one of which constitutes

the

Rhapsody in Blue

. Listeners over the past

nine-plus decades have de ned this music in

other terms—an American classic.

–Program notes ©

Todd E. Sullivan

Marvin Hamlisch

George Gershwin at the piano

Announcement for Paul Whiteman’s 1924

“Experiment in Modern Music” at Aeolian Hall

Playbill

cover for

Carousel

RAVINIA MAGAZINE | JUNE 2 – JULY 8, 2018

110